Trag-e-dy (n): A drama or literary work in which the main character is brought to ruin or suffers extreme sorrow, especially as a consequence of a tragic flaw, moral weakness, or inability to cope with unfavorable circumstances —The American Heritage Dictionary

Deputy Sheriff John Marshall (writer/director Jim Cummings) has a few problems. The recovering alcoholic with anger management issues has a monster of an ex-wife, a teenage daughter, Jenna (Chloe East), he doesn’t understand, and his dad (Robert Forster in his final role), the current police chief, has heart problems. Now, just a few weeks before his dad's retirement and the start of the ski season, something is killing young women and stealing their body parts.

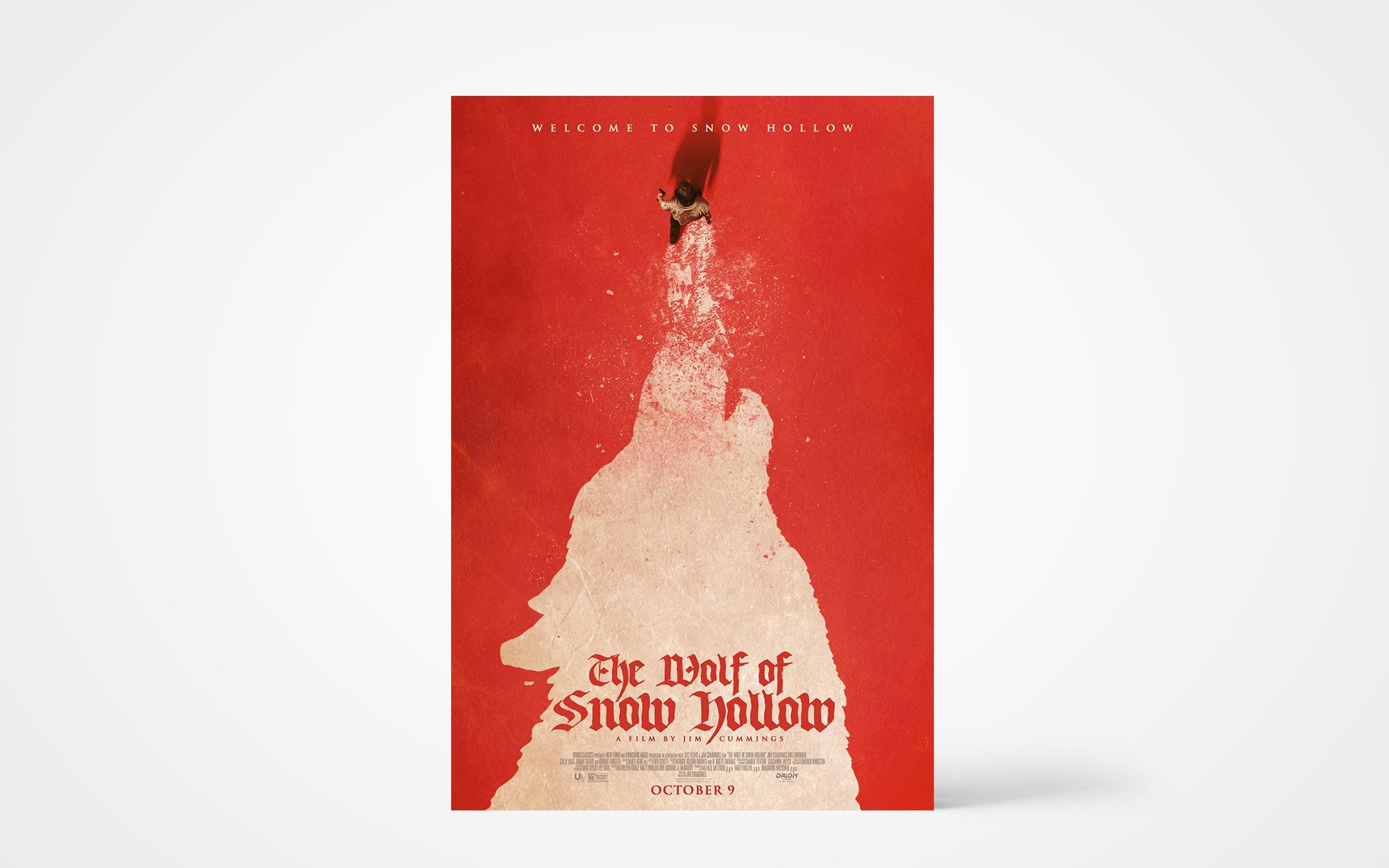

The advertising for The Wolf of Snow Hollow would lead anyone to think that it’s a comedy about a small town sheriff in denial about werewolves. It’s like Fargo with a dash of Jaws and a horror/supernatural twist. And for the first third of the movie that’s almost what we get. Unfortunately, as the movie drags on, the focus becomes less about the murder mystery and more about Marshall. Turns out, this is really an ugly tragedy in sheep’s funny clothing.

Jenna is sleeping with her boyfriend. The department’s disdain for Marshall grows. As the stress of his professional and personal life builds, Marshall falls back into old habits, drinks to dull the pain, and lashes out at the people closest to him. Meanwhile, the gruesome killings and mutilations continue, including a mother and her little girl. The initially fun movie is nowhere to be seen as profanities stack up faster than bodies and blasphemies spill out more frequently than gore.

All of this misdirection might have been forgivable if Marshall had any redeeming qualities, or if he ever stumbled onto a path of growth or redemption. Spoiler: he does not. The monster as metaphor isn’t as clever as Cummings thinks it is, either. By the end of the movie, while the literal monster has been dealt with and Marshall seems to be back on the path to sobriety, he’s even more pathetic than he was before the movie started.

We have the right to expect more from our stories and storytellers. To borrow from Neil Gaiman (who was in turn paraphrasing G.K. Chesterton), folktales are more than true, not because they tell us werewolves exist, but because they tell us werewolves can be beaten. The final note at the end of The Wolf of Snow Hollow is that while werewolves can be defeated, the real monsters of our own inner demons are just, well, what they are. Whether we consciously think it or not, we know that’s just not true. (Rated R, Orion Pictures)

About the Author

Trevor Denning is an alumni of Cornerstone University and lives, lifts weights, and spends too much time in his kitchen in Alma, Mich. His first short story collection is St. George Drive and Other Stories.