Young people aren’t growing up in the same world their parents and grandparents did. They are less active and spend less time outside, both of which contribute to worse mental health. Many kids own a cellphone before high school and are always connected to their peers via text and social media.

Modern technology allows for constant communication, which for some young people leads to thoughts of hopelessness. Some deal with bullying at school and find the harassment continues online when they get home. Or consider a student who strives for high achievement. Whenever she logs onto social media, she views the achievements proudly posted by her peers as a constant reminder of her own inadequacies.

COVID-19 has hit youth hard. While the death rate is certainly much lower in this age group, the virus and our attempts to slow its spread have had other effects on young people. Those looking for employment saw a shrunken job market. Many classes became virtual, making it difficult to ask teachers for help and to be engaged in learning. Young adults looking to nurture new romantic relationships had fewer options for getting to know each other. Statistics from Toronto’s Centre for Addictions and Mental Health show that Canadians aged 18-39 have been more likely to experience anxiety, binge drink, feel lonely, and be depressed during the pandemic than older Canadians. Loneliness and anxiety in particular differentiated this age group from the rest. It doesn’t take much imagination to understand that constant anxious thoughts during isolation can quickly lead to feeling hopeless.

As Christians, we are called to serve the least of these, and our churches do an excellent job serving some. When I was growing up, my church’s Sunday bulletin included the names of church members in the hospital, recovering from an illness, or grieving. These people would receive cards, flowers, meals, visits, and phone calls. This beautiful practice reflects the actions of the early church (Acts 2:42-47).

But our idea of who might need such compassion could be expanded. It might be hard to see, but there are young people experiencing anxiety, loneliness, and hopelessness in our congregations. They are also “the least of these.” Caring for a struggling young person might include assistance with a college application, helping make employment connections, or finding tangible ways to treat young, single individuals as equal members in the body of the Christ.

One way to start is by simply approaching an individual after church (or, in a time of pandemic, reaching out via text) and asking questions around how school is going or vocational interests, and offering to provide help where appropriate. Leaving the conversation by handing out an email address can be an act that continues the relationship.

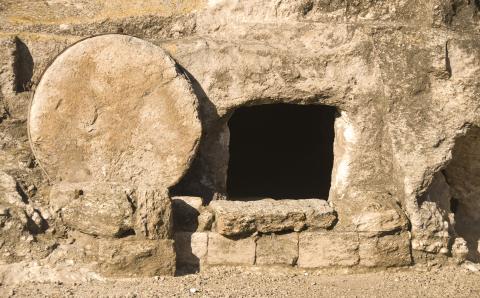

Our tangible care should grow from the hope that is fundamental to our Christian worldview— something we can share with our youth. We can express that we are children who are tenderly loved by the God of the universe. We can share that God is always renewing and redeeming his creation, including those he created on the sixth day. We can point to countless moments in Scripture where humanity’s failures and pain are followed by God’s covenantal love, which causes God to reach out to retrieve his hopeless, lost sheep.

Some people’s situations make it difficult for them to relate to the hope we have in Jesus. That’s OK. They might be ready to hear only that “all who are weary and burdened” can find rest in Jesus. Sharing this message and being like Christ simply with your presence might be all that’s required.

Challenges:

1. Young adults: Think of someone from your church community who needs encouragement. Pray for them. Even if they’re not your own age, reach out to them.

2. Older adults: Choose a young adult in your community. How can you connect with them?

About the Author

Adam Vanderleest is in his final year of medical school at Western University. He loves experiencing God’s creation. He and his wife, Katherine, worship at Talbot Street Church in London, Ont.