I remember when my youngest daughter was a newborn. Holding her in my arms, I was flooded with a host of emotions, from joy to anguish. Joy at the beautiful life in my arms; anguish that she would live her life at a distinct disadvantage. She was born with Down syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes developmental and cognitive disabilities. My wife and I went through a roller coaster of emotions. Even though we were warned of the possibility, and had read up on the disability, we were still uncertain and fearful. What will become of her? we asked ourselves. Will she have a happy life? Will she suffer? Can she go to school? How will she cope? How will her sisters cope? How will we cope?

Prior to her birth, we had decided to name her “Mathea,” a name derived from Hebrew for “gift of God.” I wanted to remind myself that her disability does not define her. She is, first and foremost, God’s gift to us. Her disability is part of that gift, even when it doesn’t feel that way to us. Partly thanks to her, I now look at Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection in a new way.

Resurrected Scars

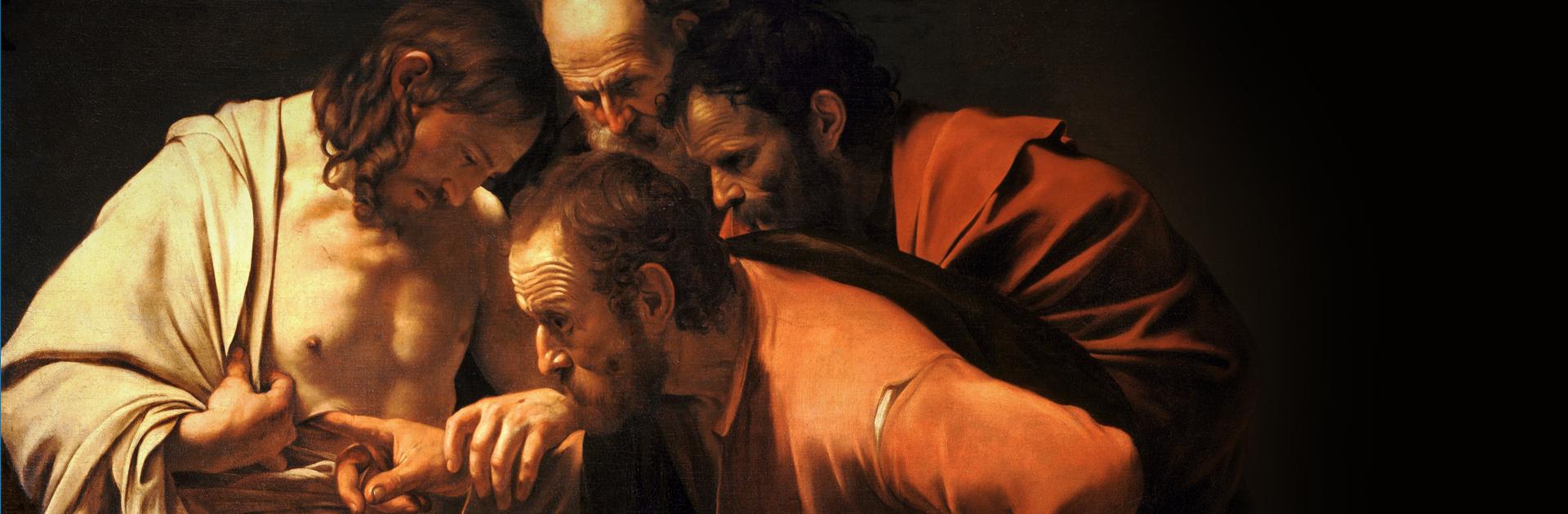

I used to imagine Christ’s resurrected body, and hence our own resurrected bodies, to be perfect and glorious, without any flaws. Yet Scripture clearly records that Jesus’ resurrected body carried the scars where the nails were driven and where the spear pierced (John 20:24-28; Luke 24:40). What does it mean for his resurrected body to still have those scars? True, those scars helped Jesus’ disciples to verify his identity. But could they not have recognized him through other means?

If Jesus’ glorious and imperishable resurrected body (1 Cor. 15:42-44) is a symbol of perfection, then what is God telling us in preserving what seems like marks of imperfection in the resurrected Christ? I don’t pretend to know fully, but here are some possible implications.

Redefining Perfect

First, perhaps God’s idea of perfection differs from ours. God may not place the same value as we do on athletic, slim, muscular, toned bodies. Our culture’s models of the perfect body, displayed in movies and popular media, are unrealistic and oppressive. People with disabilities are often made to feel that their impaired bodies are “not perfect,” if not downright cursed.

The resurrected Christ’s impaired hands and feet, therefore, suggest that disabled bodies are still vehicles of God’s glory and resurrection life. In God’s eyes, people with disabilities are as perfect as everyone else. If the resurrected Jesus is the ultimate image of God (Col. 1:15), and he bears the marks of impairment, then people with disabilities are also fully imagebearers. As theologian Nancy Eiesland points out in The Disabled God, the resurrected Jesus’ marks of impairment reveal “the reality that full personhood is fully compatible with the experience of disability” (p. 100).

So why do we continue to have typically-abled people as the spiritual norm in our minds and imaginations? When we plan or design worship, for instance, who do we have in mind? Should we still think that being non-disabled is inherently a blessing, implying that the reverse is inherently a curse?

Solidarity with Our Disability

Second, Jesus displayed solidarity with people with disabilities when he was resurrected with scars. In fact, this solidarity occurred even before the resurrection.

If we define disabilities as impairments that prevent us from doing what our peers can do, then Jesus’ incarnation as a human being can be seen as a disability. When Jesus, the Son of Almighty God, the second person of the Holy Trinity, became a helpless baby, he was confined to a singular space and time. Unlike God the Father and God the Holy Spirit, Jesus could no longer be everywhere and anywhere (omnipresent) during his life on earth. His human body prevented him from doing that. During his earthly life, Jesus could not do what his divine peers—God the Father and the Holy Spirit—could do. Jesus was, temporarily, the “disabled” God.

Similarly, in his crucifixion, the Son of God suffered death, whereas the other two immortal persons of the Holy Trinity stayed immune to death. On the cross, Jesus suffered torture, flesh torn by whips, nailed hands and feet rendering him immobile, his side pierced. On the cross, Jesus was God-with-us even in our disabilities and disfigurements. And when we would most expect all marks of suffering, pain, torture, injustice, and death to disappear, the resurrected body of Christ retained the scars.

If God chose to be in solidarity with our vulnerability and our disabilities, why do we overly value independence, self-assertion, and power? Why do we so often view ministry and mission as coming from positions of power, authority, and strength? Could we instead see ourselves ministering from a posture of vulnerability, identifying with the sufferings of others?

Resurrection Hope

Third, even though the scars remain, they do not seem to impede the resurrected Jesus’ movements and functioning. The resurrected Christ still used his hands to break bread and his feet to walk miles (Luke 24:13-32), when those injuries would have impaired any other human being. (Archaeological evidence suggests the ancient Romans would have driven nails through the heels during crucifixion. And scholars debate whether the nails went through the anatomical wrists rather than the hand’s palms.) Somehow, through the miracle of God’s resurrection power, those impairments were transformed in some way. Even though they remained visible, as the apostle Thomas verified, they no longer prevented Jesus from living life to the fullest.

Who knows? Perhaps, our current disabilities will be similarly transformed when we inherit our resurrected bodies. Even if marks of our disabilities remain, with transformed resurrected bodies and within a redeemed community in a redeemed new creation, they would no longer prevent us from living life to the full (John 10:10). This gives us hope.

I have wondered what my daughter Mathea will be like in her resurrected body in the new heaven and earth. Will she still have Down syndrome? If not, will she still be the daughter I know and love? Because of Jesus’ resurrected scars, I have hope that even if there are still imprints of her disability, she will still be identifiably Mathea and living life to her fullest!

That is also the resurrection hope for all of us. As the Heidelberg Catechism teaches, “Christ’s resurrection is a sure pledge to us of our blessed resurrection” (Q&A 45). As we meditate on our “disabled” Savior’s life, death, and resurrection, we can be filled with hope in the God who is with us in our weaknesses and disabilities, who dignifies our disabilities with God’s glory, and who delivers us from the sinful world’s barriers and discriminations.

More Resources

Disability Concerns resources website (crcna.org/disability/resources)

Erik W. Carter, Including People with Disabilities in Faith Communities (Paul H. Brookes, 2007)

Thomas E. Reynolds, Vulnerable Communion: A Theology of Disability and Hospitality (Brazos, 2008)

Nancy Eiesland, The Disabled God: Toward a Liberatory Theology of Disability (Abingdon Press, 1994)

Web Discussion Questions

- What are your experiences with disabilities and people with disabilities? How did those experiences make you feel?

- Have you ever wondered about your resurrection body? How have you imagined it might be or look like?

- How can we better involve people with disabilities in the life of the church? How well does your church do?

- Why do we tend to avoid vulnerability and weakness?

- How do you derive hope from Christ’s resurrection? What else gives you hope?

About the Author

Shiao Chong is editor-in-chief of The Banner. He attends Fellowship Christian Reformed Church in Toronto, Ont.

Shiao Chong es el redactor jefe de The Banner. El asiste a Iglesia Comunidad Cristiana Reformada en Toronto, Ont.

시아오 총은 더 배너 (The Banner)의 편집장이다. 온타리오 주 토론토의 펠로우쉽 CRC에 출석한다.

You can follow him @shiaochong (Twitter) and @3dchristianity (Facebook).