As I Was Saying is a forum for a variety of perspectives to foster faith-related conversations among our readers with the goal of mutual learning, even in disagreement. Apart from articles written by editorial staff, these perspectives do not necessarily reflect the views of The Banner.

In the summer of 1902, Alice Seeley Harris stepped out on her porch to meet with a sobbing man who had arrived at the missionary compound in the Congo Free State (now, Democratic Republic of Congo) while her husband was away. So unsteady that he needed two men to help him walk, the visitor handed Alice a package wrapped in plantain leaves.

Recounting the moment 63 years later to an audience in Surrey, England, Alice said, “Their eyes were fixed steadily upon me as I unwrapped the parcel. I opened it with greater care than was usual because I was not sure what I was in for, given the way they looked at me with such burden etched on each face. To my own horror, out fell two tiny pieces of human anatomy; a tiny child’s foot, a tiny hand.” (According to Lockner Holt records in Surrey, England.)

The man, Nsala of Wala, had failed to gather his rubber quota for the day, and Belgian-appointed overseers had killed and eaten his wife and daughter, then given Nsala the severed limbs as tokens of his punishment. Nsala had brought the grisly remains to Alice, a missionary with a British Baptist missionary society, in despair and desperation. In her own act of despair and desperation, Alice decided to take a picture.

She brought out her camera, a rare device in that time and place, and captured an image that would eventually help undermine the authority of King Leopold II of Belgium, who had been brutally oppressing the people of what was then known as the Congo Free State. Alice’s photo of Nsala with the remains of his daughter and other images documenting Belgian brutality helped spearhead reform efforts in the region.

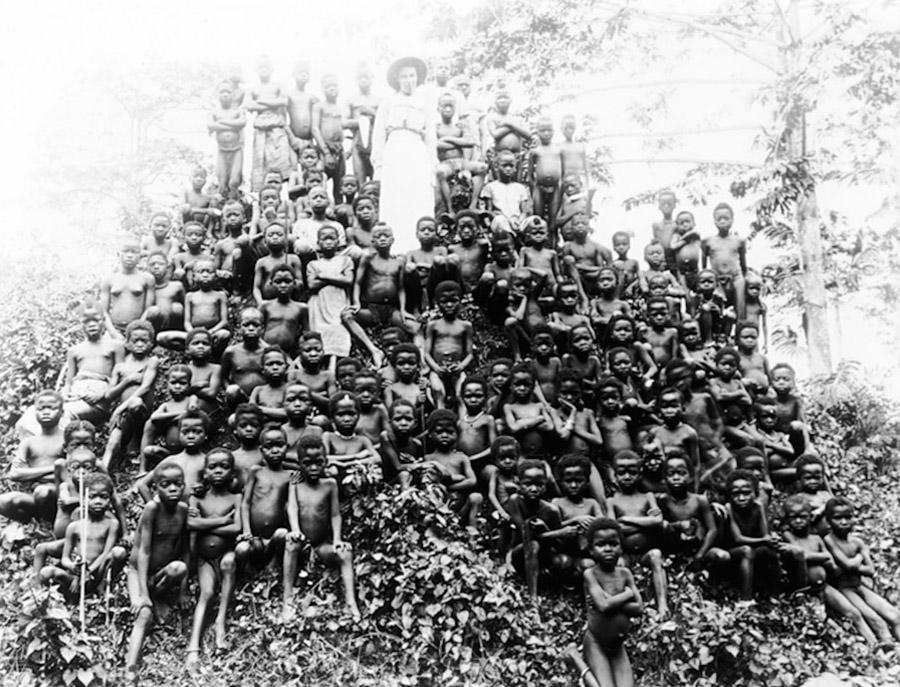

Although few today remember Alice’s story, historians recognize her as one of the first people to use photography in a human rights campaign. In an era when women were expected to be submissive and passive, this tiny missionary wife used the tools at her disposal to expose suffering and cruelty in a part of the world that rarely got much attention. At the turn of the 20th century, it was not easy to access a worldwide audience, and photography was rare and prohibitively expensive. Racism, abuse, and neglect could occur and continue in near-isolation with concerned whistleblowers few and far between. But the Holy Spirit convicted Alice that she had been sent to the Congolese people for “such a time as this” (Esther 4:14), and that she should rise up to be a voice for the persecuted.

Blazing a Trail

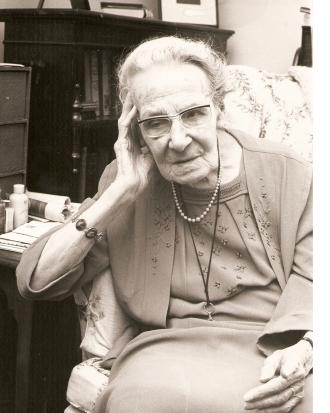

Alice Seeley Harris was born in 1870 and raised in Somerset, England, by middle-class parents who were devout Christians and activists for improving the lives of the people around them. From an early age Alice was concerned by child labor and poverty, having witnessed poor children working in the factory where her father was employed.

Alice yearned for more than the typical role of wife and mother and found a like-minded Christian man in John Hobbis Harris. Four days after their marriage in 1898, Alice and John set sail toward what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They were planning to teach literacy and bring the gospel to isolated rural tribes.

John and Alice soon noticed unusual numbers of children and young adults who were missing hands, legs, and feet. They eventually learned that Congolese workers were often mutilated for missing rubber-harvesting quotas or other minor infractions. The unthinkable brutality was routine in the Congo Free State, which was privately owned and run by King Leopold II, who had claimed the area in 1885.

He began pursuing the harvesting of rubber when prices for the commodity rose in the 1890s. Using a mercenary army called Force Publique, Leopold harnessed the local workforce by enslaving the locals and abusing them in every way: rape, torture, murdering entire villages.

Extracting rubber was risky, as workers must climb high up in trees to get the vines that produced the sap. Force Publique would hold workers’ families hostage and chop off limbs of workers or their families as a punishment for not making rubber quotas. The brutality of the Force Publique was so horrific that it may have wiped out about half of the population in just a few years. Somewhere between a million and fifteen million people died under Leopold’s control.

But few outsiders were present to notice the brutality, so John and Alice Harris were ignorant of the conditions before they arrived in Africa. When they understood what was happening, Alice, who had packed a camera to document insects and wildlife, began taking pictures documenting the abuse of the Congolese people. Although only an amateur photographer, Alice recognized the potential of the visual medium and set out to document the human abuse, neglect, and suffering in a way that would reach the masses in a new and gripping way. Possessing an artist’s eye, she took hundreds of photos, many of them featuring victims cradling arm stumps in white linen, so the stump would stand out in a black and white photo.

Fighting for Justice

Alice and John and other missionaries undertook letter writing campaigns to expose what was happening, contacting reporters, politicians, and even the Belgium overseers in an attempt to shame them. They shipped off photography glass slides along with their letters and eventually traveled all over Europe and America, lecturing and displaying Alice’s photos. Those photos helped catch the eye of benefactors and influential people such as Mark Twain, who wrote the damning King Leopold’s Soliloquy to raise awareness of the brutality.

Shedding a spotlight on the injustice moved Alice and John away from their original ministry goals, but exposing the injustice became their mission. Finally, in 1908, King Leopold stepped away from the Congo Free State as the result of international pressure. The testimony of John and Alice and her photos played a key role in alerting the world to the atrocities.

Alice and John sacrificed and endured much as a result of their work. The Congo Free State was a physically harsh landscape with thick jungles plagued with malaria and unusual tropical diseases. After the couple began speaking out against Leopold and Force Publique, they were constantly harassed by Belgium mercenaries, and their food and supplies were intercepted at port. They were even shot at. Publicizing atrocities and depravity comes with a price.

Alice sought to meet the needs of the Congolese, but she often felt inadequate, which she confessed to an audience toward the end of her life. “How to heal that much hurt? That many hearts?” She was also known to have stated, “It was all too much to bear at times.”

But Alice believed in Hebrews 12:1 and believed that she and John must “run with perseverance the race marked out for us.” Alice knew that Galatians 5:14 says, “For the whole law is fulfilled in one word: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” and she knew she had to help her neighbors. Deeply convicted that she was following the Holy Spirit’s leading in her life, Alice developed the reputation for being fearless.

Leaving a Legacy

John and Alice did receive some earthly recognition for their services in exposing and fighting the injustice and abuse in the Congo. John was knighted in 1933, allowing Alice to claim the title of “Lady.” But earthly recognition wasn’t important to Alice, and she was known for saying, “Don’t call me Lady!” The phrase described her so well that it became the title of a 2014 biography written by Judy Pollard Smith.

Alice lived to be 100, dying Nov. 24, 1970. Throughout her long life, she demonstrated her conviction that all humans are equal under God, as important as King Leopold and his lackeys who didn’t believe Congolese lives were of any consequence at all. And Alice knew which king to follow and who sat on the most important throne.

We have her photos to remind us of the abject cruelty suffered by millions of people in the Congo. Those photos also remind us of the courageous and inspirational ways Alice worked to expose that cruelty. May those photos and the story of Alice Seeley Harris inspire us to do the same in our time and our place, using the tools that God has provided.

Micah 6:8

He has told you, O man, what is good;

And what does the Lord require of you

But to do justice, to love kindness,

And to walk humbly with your God?

About the Author

Christina Ray Stanton wrote an award-winning book about 9/11 and over 50 published articles. christinaraystanton.com/mywritings