As I Was Saying is a forum for a variety of perspectives to foster faith-related conversations among our readers with the goal of mutual learning, even in disagreement. Apart from articles written by editorial staff, these perspectives do not necessarily reflect the views of The Banner. The Banner has a subscription to republish articles from Religion News Service. This commentary by Karen Swallow Prior was published on religionnews.com on Nov. 26.

(RNS) — The November issue of The Atlantic has a feature story that has generated a lot of discussion: “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books.”

The article describes how these top-tier students, while possessing basic literacy, struggle to read a lot of books (or even one whole book) because they lack the skills—and the practice—to sustain the attention and comprehension necessary to read long, rich literary texts.

Such a development among young people has obvious implications within the context of higher education, not to mention the worlds of work and everyday life these students will later inhabit.

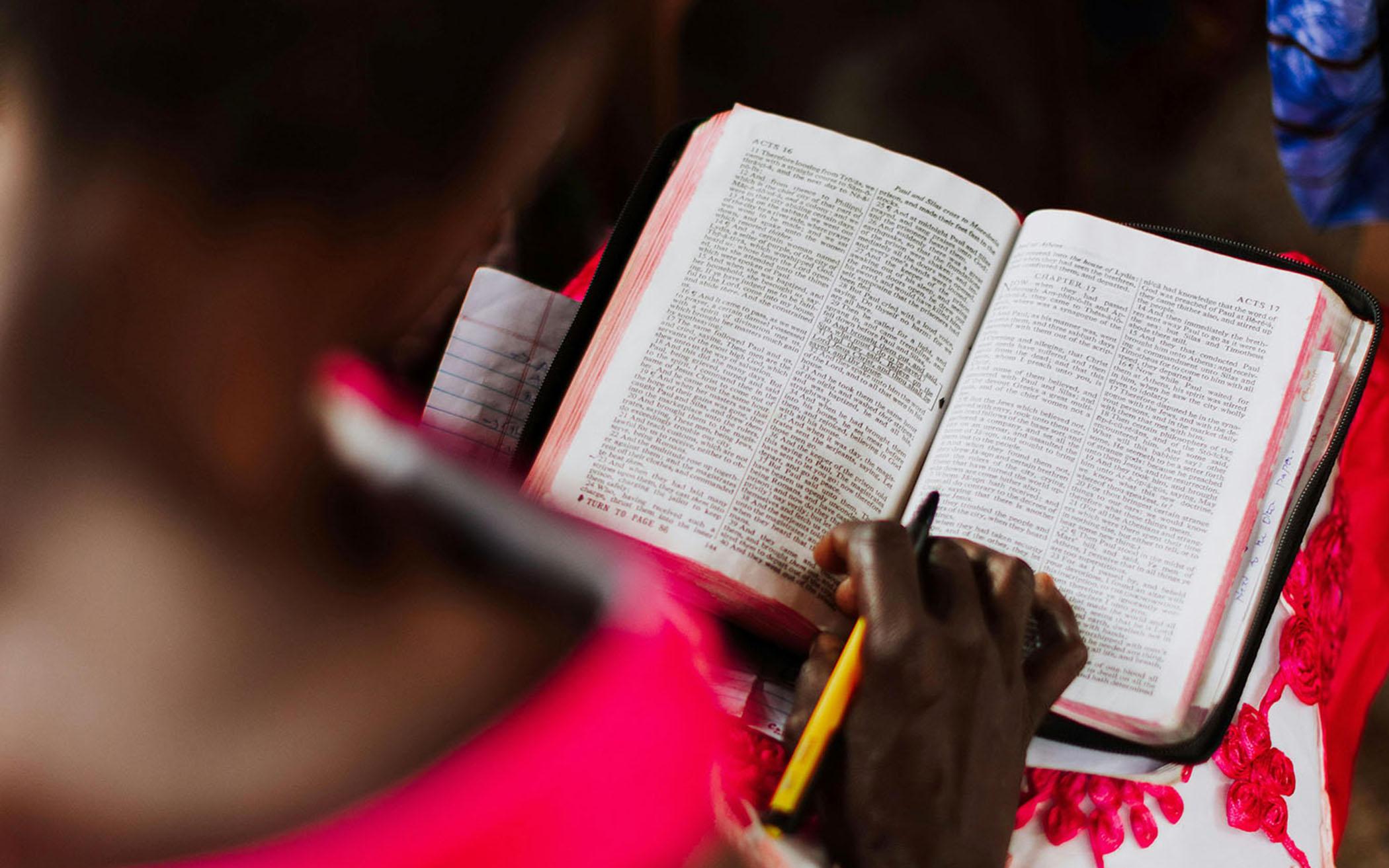

But the rise of a generation that can’t or doesn’t read books matters for the church, too. After all, if people can’t or don’t read books, how will they read the Bible? Will they read the Bible?

To be sure, hand-wringing think pieces on the decline of reading constitute a genre unto itself. It’s been tempting for a long time for educators, cultural critics, and book lovers to claim the sky is falling when it comes to reading. Annual surveys almost always show a decline in the number of books read by American adults over the previous year and over the decades. In some ways, this finding is hardly surprising. So many more options are available for leisure time. Plenty of education reporting shows children are reading fewer books in school and reading less well overall. And so much more reading material is available—and in various delivery formats—to fill the time one does spend reading. Hours spent skimming texts and social media on a phone not only don’t exercise the regions of the brain exercised during deep reading—they atrophy those areas.

The Atlantic article brings a new development to the fore in describing how college students at “elite” institutions come to college lacking both experience in reading whole books and the expectation of themselves that they should do so in a college course. “It’s not that they don’t want to do the reading,” the story explains. “It’s that they don’t know how.”

There can be no doubt that we are seeing the slow unfolding of the post-literate society predicted decades ago by communications theorist Marshall McLuhan.

Christians ought to recall that the literate society which has characterized modern life for the past several centuries was largely brought by the church. The Protestant Reformation’s emphasis on the need for all believers to read the Bible for themselves coincided with the technology of the printing press, which made mass production of the Bible (and other texts) possible. The desire of the Reformers for everyone to have access to and ability to read Scripture for themselves led to the ability to read other texts, too. Ability led to desire which led to demand which cultivated supply—of Bibles, books, pamphlets, poetry, treatises, manuals, novels, and textbooks.

The Reformers, Puritans, evangelicals, and enslaved persons who had been converted to Christianity were reading people who cultivated a literate society because they knew that the ability to read is liberating.

Eighteenth- and 19th-century evangelists and activists—people such as Robert Raikes, Sarah Trimmer and Hannah More—opened Sunday schools that prioritized teaching children to read. In the 21st century, most people—like those elite college students described by The Atlantic—have the basic skills to read but lack the experience and practice required to read deeply and well. Once again, Christians can lead the way.

One way to do so is the most natural: in church. Worship services and sermons designed to lead congregants through close reading of long texts from the Bible can actually teach reading. People have easy access today to flashing lights, stimulating videos and loud music. What people need now that churches can offer more than any other place is deep reading practice and experience. This can be done not only in worship services but also through book studies that lead readers through quality, literary texts (something I have done in my own church context).

To be sure, digital technology, like the printing press, brings its own gifts to the world. But digital media’s preference for the visual, the quick and the shallow should only complement, not replace, the deep, immersive, slow experience of reading.

Reading good books well is a formative experience. It forms our character and develops virtues (such as patience, diligence, compassion, reflectiveness, stillness, and magnanimity) that shape our hearts and souls in no lesser ways than physical exercise strengthens the body. Reading well is important for everyone and should be important to everyone, not only for students at “elite” colleges.

But for religious people especially, the loss of our collective desire and aptitude to read good books well is lamentable. Reading literary art is an expression of our being made in the image of a creator God. Cultivating the desire to enjoy good creations and being able to take delight in them also reflects the image of God in us.

Reading is an area in which the church historically has led the culture and is called to do so again. Christians have often been called a “people of the book.” The time is ripe for us to model that description and help others do likewise.

(The views expressed in this opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of RNS or The Banner.)

About the Authors

Karen Swallow Prior is Research Professor of English and Christianity and Culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and the author of Fierce Convictions: The Extraordinary Life of Hannah More—Poet, Reformer, Abolitionist, among other titles, and is editor of a series of classic literature, most recently Jane Eyre and Frankenstein.

Religion News Service is an independent, nonprofit and award-winning source of global news on religion, spirituality, culture and ethics.