I grew up among the Scandinavian immigrants of “Minnesoota,” a community marked by their elongated final vowels. In film and TV, this has become the quirky stereotype for that community. Indeed, every community has their quirkiness. But the real sign of creativity is when the quirk of a certain sub-community becomes the doorway for realizing what is common for all of us about being human.

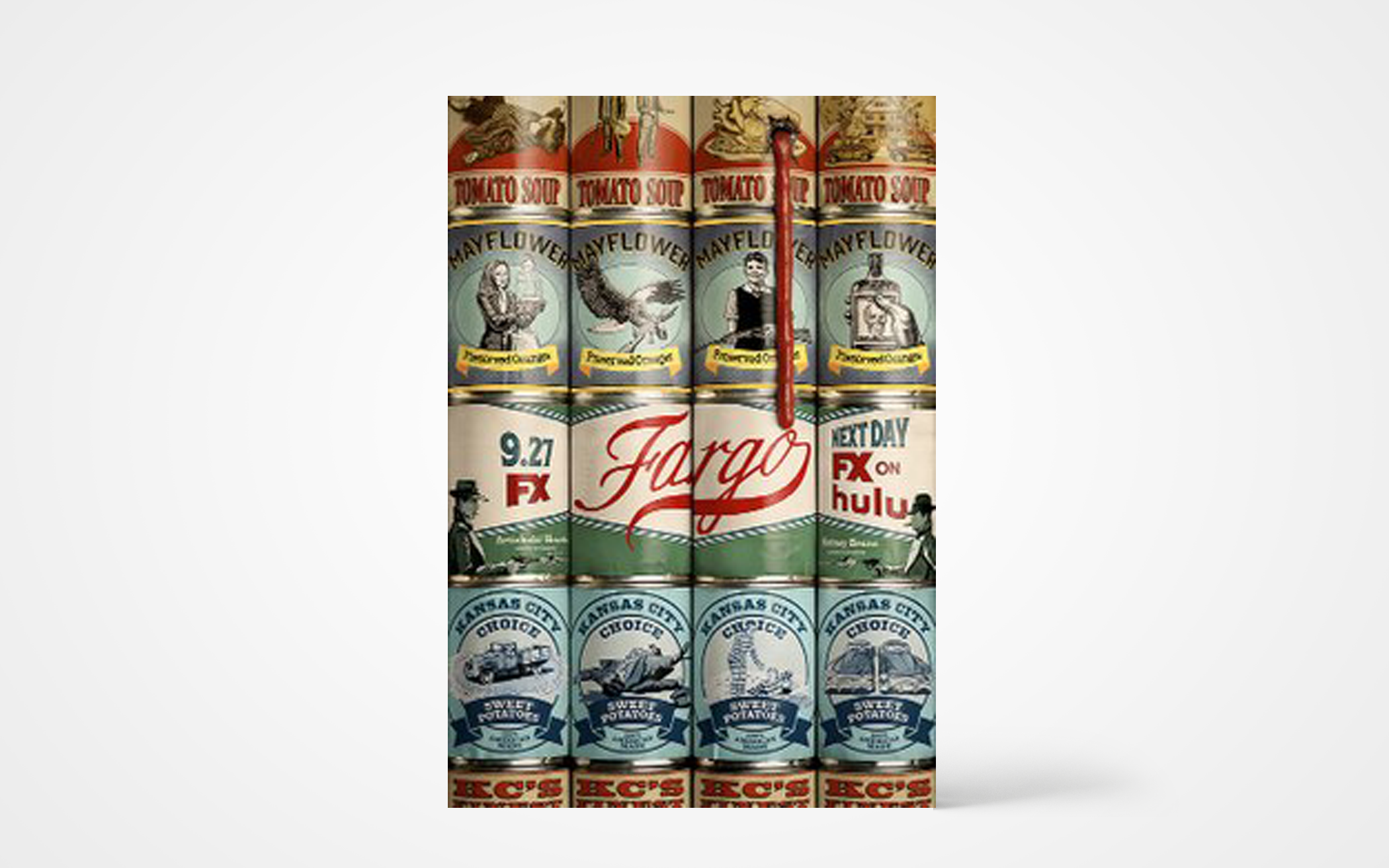

A more general upper-Midwest trait is the public politeness known as “Minnesota Nice.” But scratch below the charming smile on the surface and you’ll often find an anger borne of frustrated competitiveness. This was portrayed by Joel and Ethan Coen (“the Coen brothers”) in their 1996 film, Fargo, and Noah Hawley has translated this into a four-season TV show by the same name.

Fargo is a dark comedy (or, tragic comedy). We are presented with the oddities and stupidities of a rural ethnic community that make us laugh (the comedy part) but also the surprising crime that lies hidden and unnoticed until we’re shocked by the outbreak of unspeakable violence that reveals the true nature of life that we prefer to gloss over (the dark or tragic part).

This might be the only way to reveal something uncomfortable: cloak the despair of life in a joke we can laugh at because otherwise life is too painful to acknowledge. In this way, Fargo allows us to consider the tragic nature of life from a safer distance. In the first season, we can reflect on whether we do, in fact, want to hire a stranger to kill our high school bully—with the benefit of seeing the collateral damage it unleashes. In season two, we can imagine what it might be like to try every possible way to avoid facing up to the consequences of an accidental killing on an icy roadway—at the cost of our grasp of reality. In the third season, we can reflect on an updated re-telling of the Cain-and-Abel-like rivalry between two brothers, one spectacularly successful and the other depressingly ordinary. (After a year break, a fourth season has just been released starring Chris Rock in the American Jim Crow-era South.)

Fargo depicts routine and criminal violence without flinching—something that might unsettle sensitive viewers. But this graphic portrayal of human relationships in their most broken state (something biblical authors retain in their stories but contemporary retellings often overlook) serves to highlight one of the subtle messages contained in each season: not only can the darkness of life become unfathomably deep, but the life-giving (even redemptive) actions of seemingly insignificant people becomes, thereby, all the more profound by comparison.

One police officer’s commitment to uncovering the truth despite being consistently overlooked by her supervisor, one wife’s courageous battle with cancer though overshadowed by her heroic husband, and one teenage son’s tender love of his mother that would garner him verbal (and maybe even physical) abuse on the school playground: these characters might or might not drive the plot forward—that’s beside the point—but they are shining examples that in the midst of a world awash with evil, love, truth, beauty, and justice are still possible. Actually, they keep life worth living.

In this way, Fargo can be interpreted as an extended meditation on the biblical invitation to wisdom. From this angle, while the divine is only occasionally mentioned, God flits about Fargo’s narrative just out of sight but faithfully making life possible in the midst of death.

As Christian viewers, we could ask ourselves whether, in our own lives, we have too easily accommodated ourselves to the standardized violence of our world or whether we are courageously making life more possible for others, even if we might never show up in the spotlight. In Fargo, as in most of everyday life, the spotlight is too often reserved for the death-dealers. Content warning: violence, gore, drug use, criminal activity, sex/nudity. (FX, Hulu)

About the Author

Michael Wagenman is the Christian Reformed campus minister at Western University in London, Ont., where he invites undergraduate students to put their faith into loving service and mentors graduate students. His most recent book is The Power of the Church: The Sacramental Ecclesiology of Abraham Kuyper (Wipf &Stock, 2020).