Long ago the prophets Isaiah and Micah pointed to a future day when the nations “will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore” (Isa. 2:4; Mic. 4:3). Micah further prophesied, “Everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree, and no one will make them afraid, for the Lᴏʀᴅ Almighty has spoken” (Mic. 4:4).

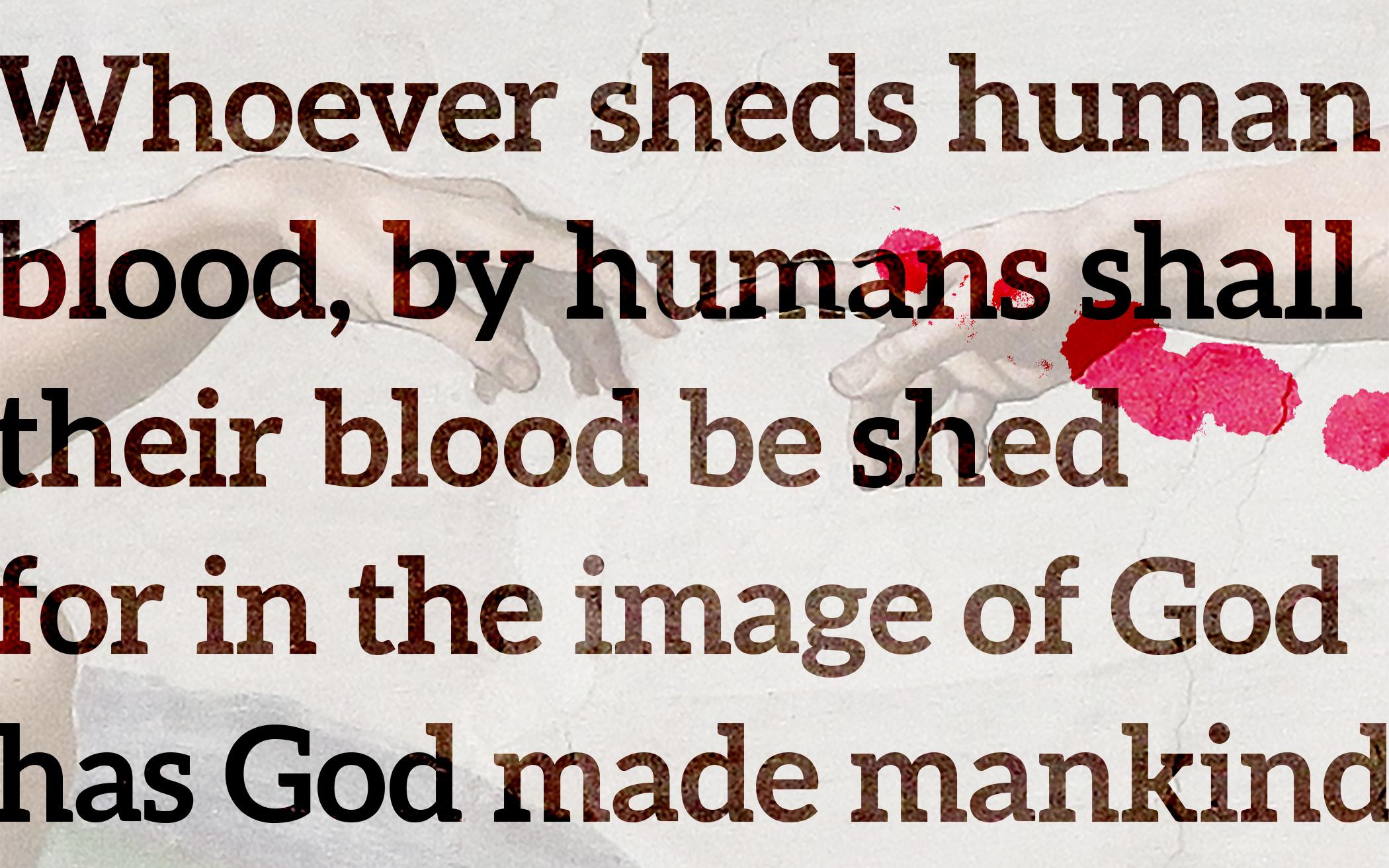

The hope of peace and security—of life—is ultimately rooted in the age-old biblical teaching that God created human beings in his own image. As such, we were made for life, not death. The cataclysmic judgment of the flood was God’s response to the sin of violence (Gen. 6:11). After the flood, God reaffirmed the sanctity of life, declaring to Noah and his sons, “For your lifeblood I will surely demand an accounting. I will demand an accounting from every animal. And from each human being too, I will demand an accounting for the life of another human being. Whoever sheds human blood, by humans shall their blood be shed; for in the image of God has God made mankind” (Gen. 9:5-6, emphasis added).

The law of Moses called for the vigorous defense of human life, but peace remained elusive even for Israel. And so prophets like Isaiah and Micah pointed to a future day of peace, security, and flourishing.

This was the dream Jesus called into being when he preached the good news that “the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Matt. 4:17). Proclaiming blessings on “peacemakers, for they will be called children of God” (Matt. 5:9), he called his disciples to the way of life-giving love.

It was no longer enough simply to avoid the act of murder. Jesus called his followers to seek reconciliation with one another at all costs (Matt. 5:21-26). It was no longer enough to restrain retaliation. Jesus commanded his disciples to serve even their enemies: “But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. . . . Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you” (Matt. 5:39-40).

Did Jesus intend these teachings to be taken literally? In The Moral Vision of the New Testament, theologian Richard Hays points out that Jesus practiced what he preached. The way Jesus lived and died gives every indication that he intended his teaching to be taken quite literally. And when one of his disciples assumed that Jesus’ prohibition of violence did not apply to moments of self-defense (or, to put it more precisely, to moments in which the life of one’s neighbor—or even one’s Lord—is under attack), Jesus cut him short. “Put your sword back in its place, . . . for all who draw the sword will die by the sword” (Matt. 26:52).

John Calvin noted that Jesus was not simply calling his disciples to stand down because he was the Messiah who had to die on the cross for the sins of the world, as is often claimed. Rather, “By these words, Christ confirms the precept of the Law, which forbids private individuals to use the sword.”

To be sure, as the apostle Paul explicitly teaches, God has authorized governments to wield the sword. “They are God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer” (Rom. 13:4). But even magistrates are not authorized to take human life with impunity. They will be held to account by the God who demands that they “uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed” (Ps. 82:3).

In 1971 a Roman Catholic pacifist named Eileen Egan described Christian teaching regarding the sanctity of life as a “seamless garment” that protects and fosters every human life from conception to the grave. Over the years many Protestant Christians have embraced this concept, at least as a general principle. Still, many Christians feel bewildered by the wide array of claims and counterclaims regarding the sanctity of life. Is abortion always wrong? Is capital punishment justified? May Christians defend themselves when attacked? In short, what does it mean for disciples of Jesus to be pro-life?

This is a massive topic, but I believe we can begin to answer this question by keeping four principles in mind.

First, contrary to popular belief, the Christian tradition does not clearly affirm that Christians may kill in self-defense. The early church father Augustine acknowledged that civil laws ought to permit the killing of an assailant in self-defense. However, he insisted, this does not mean that it is morally right for Christians to do so. There is a “powerful, hidden law” that requires a Christian to be willing to give up his earthly life and possessions for the sake of love. “How can they be free of sin in the eyes of that law, when they are defiled with human blood for the sake of things that ought to be held in contempt?”

Centuries later, Thomas Aquinas argued that a Christian may use force to defend herself from an assailant as long as her intent is not to kill but only to defend. “Such acts of self-defense, as one intends by them to preserve one’s life, do not have the character of being unlawful, since it is natural for everything to keep itself in existence as far as possible.”

Calvin warned that violence on the part of private individuals is almost always sinful. As he put it, “in order that a man may properly and lawfully defend himself, he must first lay aside excessive wrath, and hatred, and desire of revenge, and all irregular sallies of passion, that nothing tempestuous may mingle with the defense. As this is of rare occurrence, or rather, as it scarcely ever happens, Christ properly reminds his people of the general rule, that they should entirely abstain from using the sword” (emphasis added).

While all of these theologians supported civil laws authorizing citizens to defend themselves from aggressors, none of them believed that such a legal right should be conflated with the duty of a disciple of Christ.

Second, Christianity teaches that all human life is sacred. The newly conceived fetus is no less sacred than any adult or child. Those of us with disabilities or painful terminal conditions are owed the same life-sustaining love as are people who are young and healthy. Indeed, the same is true of those who would seek to harm us. This principle applies also to people who have no legal right to be present in our communities.

Historically our culture has not granted all human beings the basic rights of justice. From Dred Scott v. Sandfordin 1857 to Roe v. Wade in 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States has determined that certain classes of human beings do not qualify as legal persons and therefore do not possess ordinary legal rights.

Many Christians have rightly insisted, based on Scripture (Ps. 51:5-6) and with clear scientific warrant, that human life begins at conception. And Richard Hays points out that Jesus was never guilty of “defining marginal cases out of the human race. . . . Jesus’ persistent strategy was, on the contrary, to define the marginal cases in.”

This means that for disciples of Jesus, abortion is immoral in all cases in which it is not necessary to save the life of the mother. It also calls Christians to avoid using any forms of birth control that potentially act as abortifacients. This is a point on which Christians need to do a lot more thinking, research, and self-evaluation.

Finally, this ethic means that all forms of suicide, assisted suicide, or “mercy” killing violate God's moral principles, whether in cases of chronic pain, terminal illness, aging, loneliness, or despair. The gospel calls disciples to serve all human beings, no matter their stage of life or suffering, with life-giving love.

Third, the sanctity of human life requires us to do whatever is necessary to protect and preserve human life. The writers of the Heidelberg Catechism emphasized this point in their explanation of the sixth commandment. The prohibition of murder requires that I love my neighbors as myself, being “patient, peace-loving, gentle, merciful, and friendly toward them,” and that I “protect them from harm as much as [I] can” (Q&A 107). I am neither to harm nor “recklessly endanger” a person made in the image of God.

In short, Christ calls us to be proactive in fostering the conditions necessary for life. As Calvin put it in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, “The purport of this commandment is that since the Lord has bound the whole human race by a kind of unity, the safety of all ought to be considered as entrusted to each.” We are called to do whatever is required to “defend the life of our neighbor; to promote whatever tends to his tranquility, to be vigilant in warding off harm, and, when danger comes, to assist in removing it.”

There are few better examples of this proactive commitment to the sanctity of life than the story of the Good Samaritan. While the Levite and the priest considered their duty done, given that they had not harmed the man lying on the side of the road, the Good Samaritan “went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him.” He then committed him to the care of an innkeeper, promising, “When I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have” (Luke 10:34-35).

Many Christians have therefore discerned that the sanctity of life calls for society to care for mothers who are young, poor, or unwed just as much as it calls for maintaining the rights of the unborn. Opposing violent crime and other threats to human safety requires taking proactive steps to alleviate poverty, to enable individuals to secure education and work, and to seek reconciliation where there is conflict or mistrust. The sanctity of life requires the provision of food, clothing, shelter, and health care for people who cannot secure it for themselves. It requires society to seek the safety of those who are vulnerable to accidents, pollution, or natural disasters. Disciples of Christ should be zealous on behalf of those of us whose lives some may consider less than “productive” because of physical or mental disabilities, debilitating injuries, or lack of familial bonds. As such, we must find ways to secure the well-being of refugees, victims of injustice, and those who have no legal right to be part of our communities. Christians should be at the forefront of efforts to protect and preserve human life.

Fourth, God has established government to protect and preserve human life, and God has authorized government to wield the sword against those who take human life. To be sure, Christians will always continue to debate the best way for government to fulfill these ends. We debate policy approaches, jurisdictional questions, and constitutional concerns. And all of this we must do. We must maintain a healthy humility about what is possible in a fallen world and about the best means of achieving justice and peace. But we can never compromise our most basic commitment to the sanctity of life of all human beings, or to government’s special obligation to protect the most vulnerable human beings.

We should therefore be sensitive to the ways in which governments wage war, police communities, and administer capital punishment, always insisting that the use of lethal force must be in accord with the demands of justice (including just war principles of lawful authority, just cause, peaceful intent, proportionality, and respect for innocent life). While Scripture authorizes capital punishment as a means of retributive justice, the death penalty is never justified for a person whose guilt is unproven through a fair judicial process.

In a world of sin and death it is easy to fall into despair in light of the seeming cheapness of life. And yet we walk by faith, hope, and love, and not by sight. The reality is that pro-life discipleship requires that we ourselves become vulnerable as we pour ourselves out in life-giving service to our neighbors and enemies. For our Lord, this path ended in suffering and death, and we too are called to take up our cross. But as we walk the path of discipleship, we need only remind ourselves of this promise of Jesus: “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Matt. 25:40).

Discussion Questions

- If, as Tuininga says, it is true that “the Christian tradition does not clearly affirm that Christians may kill in self-defense,” what does that imply for Christians who are not security professionals who carry guns today?

- How does the Christian teaching that “all human life is sacred” apply to some of our current issues, including abortion, refugees, and euthanasia?

- What do you think of the author’s examples of ways Christians are called “to protect and preserve human life”?

- Since pro-life discipleship requires it, how have we become vulnerable in life-giving service to our neighbors and enemies?

About the Author

Matthew J. Tuininga is professor of Christian ethics and the history of Christianity at Calvin Theological Seminary. He lives in Wyoming, Mich. He is the author of The Wars of the Lord: The Puritan Conquest of America’s First People.