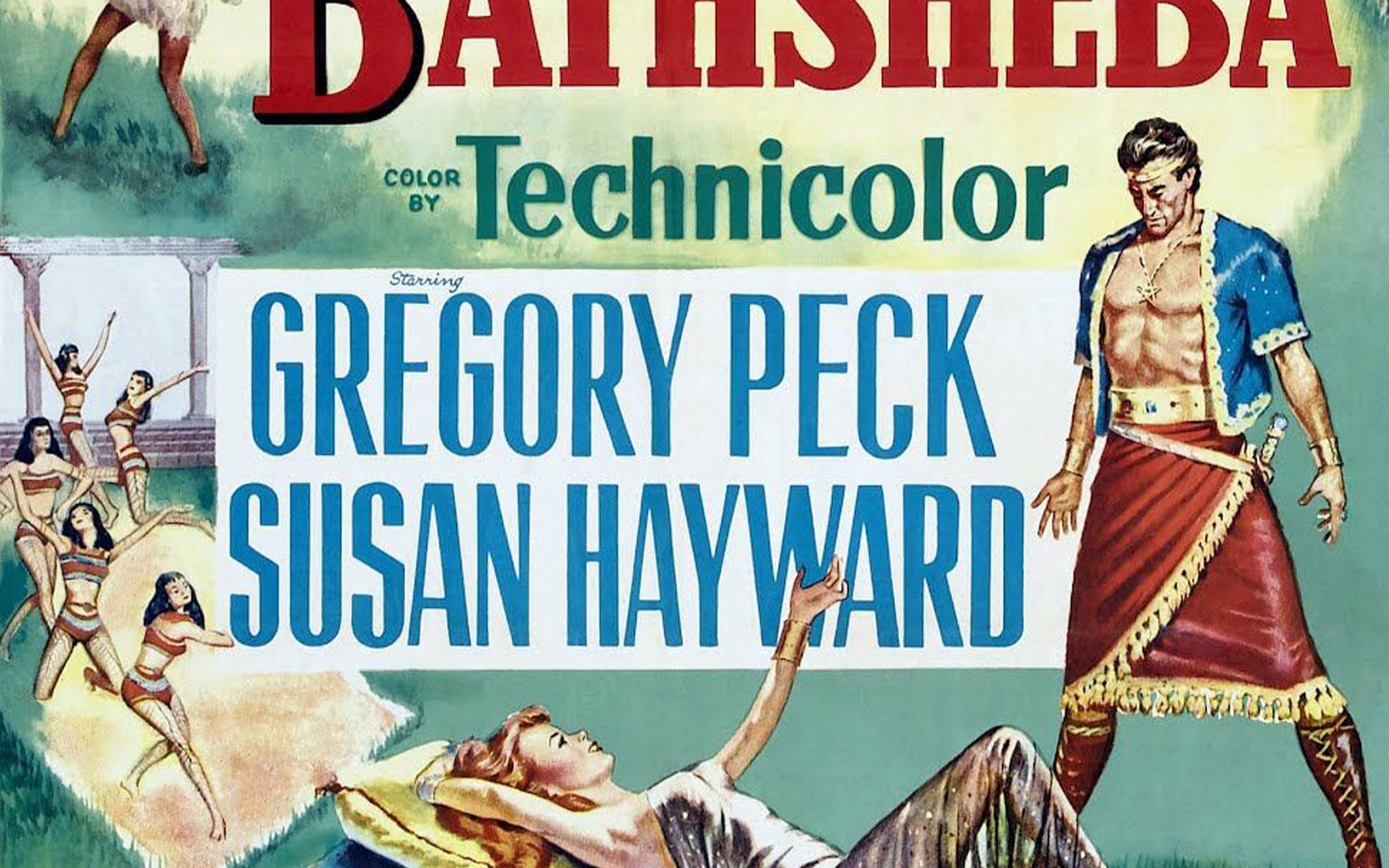

A movie poster from the 1950s shows Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward starring in the film David and Bathsheba. Muscular and bare-chested, Peck stands over a scantily clad Hayward as she reclines on a pillow. Her hand is outstretched toward him as if beckoning him closer. It all looks a little quaint and old-fashioned now, but at the time it was so racy that in some places there were reportedly riots protesting the release of the film.

Biblical narratives are often detail-sparse and economical. They tell us the bare facts—what people did and what they said—but not a lot beyond that. They don’t give us much information about what people were thinking or feeling, or what their motivations were. According to the story in 2 Samuel 11, King David saw Bathsheba taking a bath. He sent for her, she came to him, and she became pregnant. Why did David do what he did? How did Bathsheba feel about it? We just don’t know. In the film version, Hollywood capitalized on the lack of detail, giving its own spin to the story.

But Hollywood isn’t the only place people do that. We all put our own spin on Bible stories, interpreting the bare facts and connecting the dots in ways that make sense to us. The way we do that reveals important things about us: our assumptions, our prejudices, our cultural norms, and our worldview.

Take, for example, what one biblical commentator says about Bathsheba: “One cannot but blame her for bathing in a place where she could be seen. . . . Not, of course,” he quickly concedes, “that this possible element of feminine flirtation is any excuse for David’s conduct.” He continues to guess about Bathsheba’s state of mind: “Her consciousness of the danger into which adultery was leading her must have been outweighed by her realization of the honor of having attracted the king” (Hans Wilhelm Hertzberg, I & II Samuel: A Commentary, 309-310).

Put this side by side with the take of author April Westbrook, who writes that many houses at that time were built with an inner courtyard completely surrounded by walls. You would have every reason to think you had privacy there, having no idea that someone might be spying on you from the rooftop of a nearby building. And it doesn’t matter who’s spying on you—whether a king or a pauper, it’s not an honor. It’s a violation. Furthermore, going from a solitary wife in a noble household, as Bathsheba was, to a low-ranking wife in a king’s harem was not exactly a step up in the world, and not the stuff of girlhood dreams by any stretch. Connecting the dots in a very different way, Westbrook concludes: “Bathsheba is a respected and pious Israelite woman whose life is interrupted dramatically by the king, who decides one night to engage in voyeurism” (Westbrook, And He Will Take Your Daughters, 124).

Reading these two accounts one after the other made me think back on my own visualization of the story. I’m kind of embarrassed to say it now, but for some reason I had always pictured Bathsheba on a roof, too, just a couple doors down from David, taking a bath in plain sight of God and everyone. Why did I picture it that way? I didn’t set out intending to blame the victim, but I sort of did, didn’t I? Thanks to the #MeToo movement, I’ve started connecting the dots in very different ways. Of course, I can’t say for sure what Bathsheba was thinking or feeling. None of us can. But in the absence of more information, without apology I’ll take the part of the one who had less power.

It’s common to see this story under the heading “David’s Adultery.” I wonder if that whitewashes it too much. Why not call it “David’s Abuse of Power”? Or even “David’s Sexual Assault”? What about “David’s Child Abandonment,” or “David’s Murder”?

How about all of the above? It’s a terrible story no matter what you call it. It begins with David’s men going to war while David remains at home. David has reached the height of his power. He can sit back while his underlings do the fighting for him. While they are off risking their lives, he can take an afternoon nap on his rooftop couch. From that vantage point, he spots a beautiful woman taking a bath.

She is married, and her husband is one of David’s loyal soldiers, but that doesn’t stop David from summoning her to the palace. The text doesn’t allow us to romanticize what happens next. “The action is so stark,” writes Walter Brueggemann (First and Second Samuel, 273). “There is nothing but action. There is no conversation. There is no hint of caring, of affection, of love—only lust. David does not call her by name, does not even speak to her. At the end of the encounter she is only ‘the woman’”—a nameless object, David’s personal pornography that he clicked away from as quickly as he had clicked onto it.

One wonders if David would have given Bathsheba a second thought after that, and the answer is probably not. But then the news came that she was pregnant, which meant David had a problem on his hands. What he had done would become public. So David has Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, called in from the battlefront. David tries to trick him into sleeping with his wife so David could pass the baby off as Uriah’s. David is ready to abandon his own child to hide his sin.

But Uriah is a man of integrity. He refuses the offer to be comfortable at home while his fellow soldiers are risking their lives. He doesn’t cooperate with David’s plan. Eventually, David sends him back to the battlefront with orders to the commander to put him on the front line and then abandon him to the enemy. This time David’s plan works. Uriah is killed, and David takes Bathsheba as his wife.

Eventually, of course, David does confess his sin, but not until he is backed into a corner. He had a lot of help and support in waiting so long to come clean. David did not commit his sins alone. He needed someone to bring Bathsheba to him and carry messages back and forth. He needed the commander of his army to take care of Uriah. He needed everyone who saw what he was doing to stay silent and not speak up for the victims. David had a lot of help from a lot of people.

We’ve seen a lot of powerful figures fall from grace this past year—actors, television personalities, politicians, comedians, even chefs. For a while it seemed as if every day there was another person disgraced because of allegations of sexual assault or harassment. What was even more surprising than the accusations, though, was the length of time such behavior had gone on. In some cases it was an open secret. Everybody knew. It’s just that the perpetrators weren’t held to account.

That’s because they had a lot of help. In many cases, the accused were respected, successful people who were doing impressive work in their fields. They were surrounded by people who had a vested interest in having them continue that work and who were willing to minimize or turn a blind eye to bad behavior as a result. They were surrounded by people who may not have approved, but who also didn’t challenge.

The same was true in David’s case. Uriah and Bathsheba hardly stood a chance. All the forces of power and the status quo were working against them. David was surrounded by people who were cooperating with him, who were helping him cover it up, who were turning a blind eye, or who just stood by and did nothing.

But there was someone who did not stand by and do nothing: God. If you think about it, God might have been the one in this story most interested in covering up David’s sin. God spent most of the previous 30 chapters of the Bible bragging about David, whom God called “a man after my own heart.” God worked tirelessly behind the scenes to bring David to exactly this place and this position, because God had plans for David and his dynasty. God had a vested interest in David being a respected, successful king. If David fell from grace, quite frankly it’s God who looks bad. If this got out, it might make God seem like a poor judge of character who backed the wrong guy. It was in God’s best interest to bury this story.

Yet God did not bury it. In fact, God did just the opposite. God saw to it that the story of Uriah and Bathsheba would be told and retold for 3,000 years. This tells me that God has an awfully long memory for injustices done, for abuse suffered, for lives ruined by exploitation or cut short by violence.

There have been countless stories like this in the history of humankind: Countless victims who never stood a chance because they were too young, or too weak, or too poor. People who had all the forces of power and the status quo working against them and no one to speak up for them. People just like Bathsheba and Uriah. So many of those stories seem lost. Perhaps they were never told in the first place, or they were ignored or forgotten. Justice was never done. Abusers were never called to account. Or if they were, it was too late. The damage was already done.

Those stories aren’t just “out there.” They are in our congregations. In the U.S., one in four girls will be sexually abused before turning 18, and one in six women will experience some kind of sexual assault. One in six men, too, will be the victim of sexual abuse or assault.

When I first heard those numbers, they seemed so high. Then I became a pastor. I started hearing people’s stories—my congregants’ stories. I thought about the size of my church and the number of stories I was hearing, and I realized those numbers rang true. I’ve learned that even in a church, we need to be careful. There are a lot of stories.

What the story of Uriah and Bathsheba tells me is that none of our stories is lost to God. There is a reckoning for Uriah and Bathsheba. God has not forgotten what happened to them, not in 3,000 years. God does not forget your story either.

And God does more than remember. God has the power to redeem. In his execution on the cross, Jesus was condemned by the world. He hadn’t done anything wrong, but up against the forces of religious and political power, he didn’t stand a chance. He died, a victim of violence, abuse, and murder. It looked for all the world as if that was the end of the story—another casualty of a broken, unjust system.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. God raised Jesus from the dead. The resurrection was God’s judgment on the world. In the resurrection, God looked at the miscarriage of justice that put Christ on the cross, looked at all the people who had colluded to harm an innocent man, and said, “You were wrong. You should not have taken his life. So I’m going to give it back to him.” And God, being God, had the power to do just that.

After all is said and done, God still has the final word. After it’s too late and the damage has already been done, God still has the final word. Whatever your story is, God still has the final word. Above all the forces of power in this world stands the power of God. Psalm 145 is a beautiful picture of what that power looks like in action: “The Lᴏʀᴅ upholds all who are falling, and raises up all who are bowed down. . . . The Lᴏʀᴅ is just in all his ways, and kind in all his doings. The Lᴏʀᴅ is near to all who call on him, to all who call on him in truth. He fulfills the desire of all who fear him; he also hears their cry, and saves them” (Ps. 145:14, 18-19, NRSV).

That’s the God who with goodness and power redeems us. That’s the God who with goodness and power gives us back our dignity, our wholeness, and even our very lives, no matter what stories we have to tell.

Discussion Questions

- How have you previously visualized and understood the story of Bathsheba and David?

- What can be done in churches to prevent and reduce the shocking statistics on sexual abuse?

- David was able to commit his sin with a lot of help from a lot of people. How do we cultivate a culture in our churches that fosters accountability and reduces silence?

- How does it help victims of abuse to be reminded that God does not forget, and God has the final word to all the injustices in our world?

About the Author

Christina Brinks Rea is the pastor at Church of the Savior CRC in South Bend, Ind.