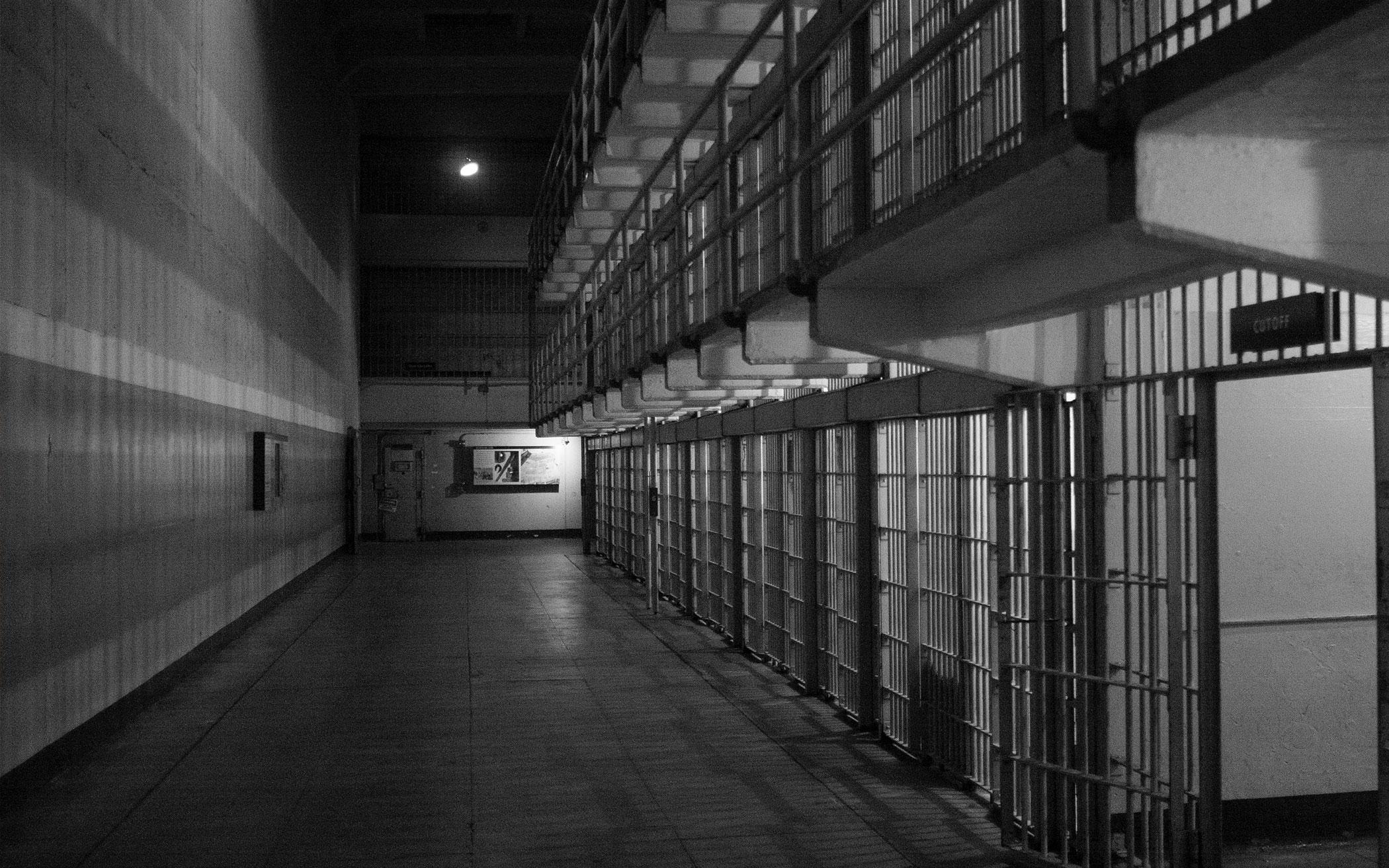

In the United States and Canada, we hand over to governments the job of responding to crimes. After a crime is committed, governments primarily ask: Who is guilty? How should that person be punished?

The restorative justice movement began with Mennonite Christians in search of a better response. They started with a biblical understanding of justice and shalom, centered in the need for accountability, reconciliation, and peace. With these goals in mind, they concluded that after a crime takes place, the most important questions to ask are: Who was hurt? And how can that harm be repaired? Those questions focus attention on victims’ needs and the repair of the community.

Restorative justice advocates understand the importance of punishment for wrongdoing. They also know that placing primary focus on healing the victim of a crime—and not just on the consequences for the offender—leads to a very different set of responses to crime. Asking restorative questions leads to empowering victims and other members of the community who have been affected by the crime.

The first step in a restorative justice approach is to really listen to victims. It’s often our instinct to turn to an “expert” in response to a problem. We hire doctors to heal, accountants to manage money, teachers to teach. And because our government is in charge of responding to crimes, responses come from government “experts”—judges and prosecutors who are trained to answer questions of guilt and punishment, not questions of harm and healing. But as to the harm suffered after a crime, it is the victim who is truly the expert.

Governments’ focus on guilt and punishment means that even when the victim is asked for input, the requests are scripted and formalized, designed to shape the victims’ responses. We’re familiar with courtroom sentencings where victims are brought forward to answer the question “How should we punish the offender?” This drama typically happens at the end of a process that allows victims no contact with an offender, very little input into the case, and only a short time to make a public statement. As a result, victims’ responses tend to focus on punishment—and so the government’s response to crime begins and ends with punishment.

There is a better way to listen to victims. If we take the time immediately after a crime to ask victims what they want, without preconceptions or an agenda, victim responses vary but often take a similar shape.

First, victims tend to wonder: Why did this happen to me? Being the victim of a crime disrupts the feeling that we are in control of our lives, and it often makes one feel unsafe. People don’t choose to be victims, so anything they can do to understand why the crime happened to them can help re-establish a feeling of control. Knowing why a robber chose my house and not the house next door, why a mugger chose me, why the person driving a car ran into me are all really important questions. Answers to “why” questions usually top the list of victims’ expressed needs.

Second, victims have a strong desire to tell the offender how much the crime hurt them. Victims of a break-in want to tell the thief that they and their entire family no longer feel safe at home. Victims of an assault want to tell the assailant that they fear assault all the time. Victims of embezzlement want to explain how that theft broke a trust and ended a valuable relationship.

Third, victims almost always want a real apology from the offender. They want to know that the offender understands the damage he or she did and that the offender is sorry. In order for that to happen, victims need to tell the offender about the harm done and have that information really sink in. Victims don’t want an apology that was coerced. There’s no worse format for an “apology” than a courtroom sentencing, where anything the offender says looks like a ploy to get a lighter sentence and where a victim has to talk about painful, often embarrassing things in public.

Victims tend to express their needs for asking, telling, and hearing an apology before expressing desire for punishment. That’s not to suggest crimes don’t deserve punishment, or that victims can’t or shouldn’t ask for punishment. It just means that all those other needs—which can’t be met by any government expert—come first. They can only be met through an encounter with the offender. That’s why victims who are offered the opportunity to have a safe meeting with the person who harmed them tend to want to ask why, to describe their hurt.

Despite what we see on shows that dramatize offenders as remorseless sociopaths, most offenders understand that what they did was wrong. Many are sorry for what they did and would fix the harm they caused if they could. Most offenders are willing to meet victims and revisit the crime and its aftermath. So why isn’t the opportunity for such an encounter offered as a matter of course?

It goes without saying that such encounters have to be handled carefully. Cases where there is a large disparity of power or where an encounter might lead to more victim trauma or where an offender is not willing to take responsibility are all situations in which an encounter may not be a good idea.

But if the encounter focuses on the needs of the victim, it can empower the victim and begin the process of healing. Conversations that include a discussion of consequences and amends may serve as a first step along the road to forgiveness. They might also provide a real opportunity for offenders to understand the magnitude of the harm they caused and to develop empathy with their victims. Such empathy is the best hope for preventing the offender from repeating the behavior.

Forgiveness is hard. It is also deeply personal. As much as we may value forgiveness, we have to be very careful not to push it on anyone. For that reason, restorative justice practitioners are careful to focus on a process of listening to and empowering victims. They don’t expect specific results. Victim healing is the goal of restorative justice, and that healing has to happen on a path where the victim is leading.

Offenders are different. Offenders offended, and restorative justice practitioners always work toward offender accountability, empathy, and reparation. Ideally, movement toward healing and real accountability can also begin the work of reconciliation and can involve the broader community, which is also hurt by offenses. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for example, was modeled on restorative justice principles to heal not just victims, but an entire country scarred by injustice.

Restorative justice principles can be used in any situation involving hurt that needs healing: family fights, workplace conflicts, school discipline issues, and even national traumas. Wherever a community needs to be repaired, there is a role for restorative justice.

Discussion Questions

- What comes to your mind when you hear the phrase “restorative justice”?

- What are some aspects of biblical justice and shalom you are aware of that might contribute to the emphasis in restorative justice on repairing harm caused?

- Can you envision restorative justice principles applied to conflicts in the local church community? What might it look like to focus on the needs of victims rather than punishing the guilty?

- What one restorative justice principle will you choose to practice personally in your life for resolving conflicts?

About the Author

David LaGrand is a Michigan State Representative from Grand Rapids serving his second term. He sits on the House Judiciary Committee as Minority Vice Chair. David has been involved in jail ministry for 30 years and is a commissioned pastor in the Christian Reformed Church.