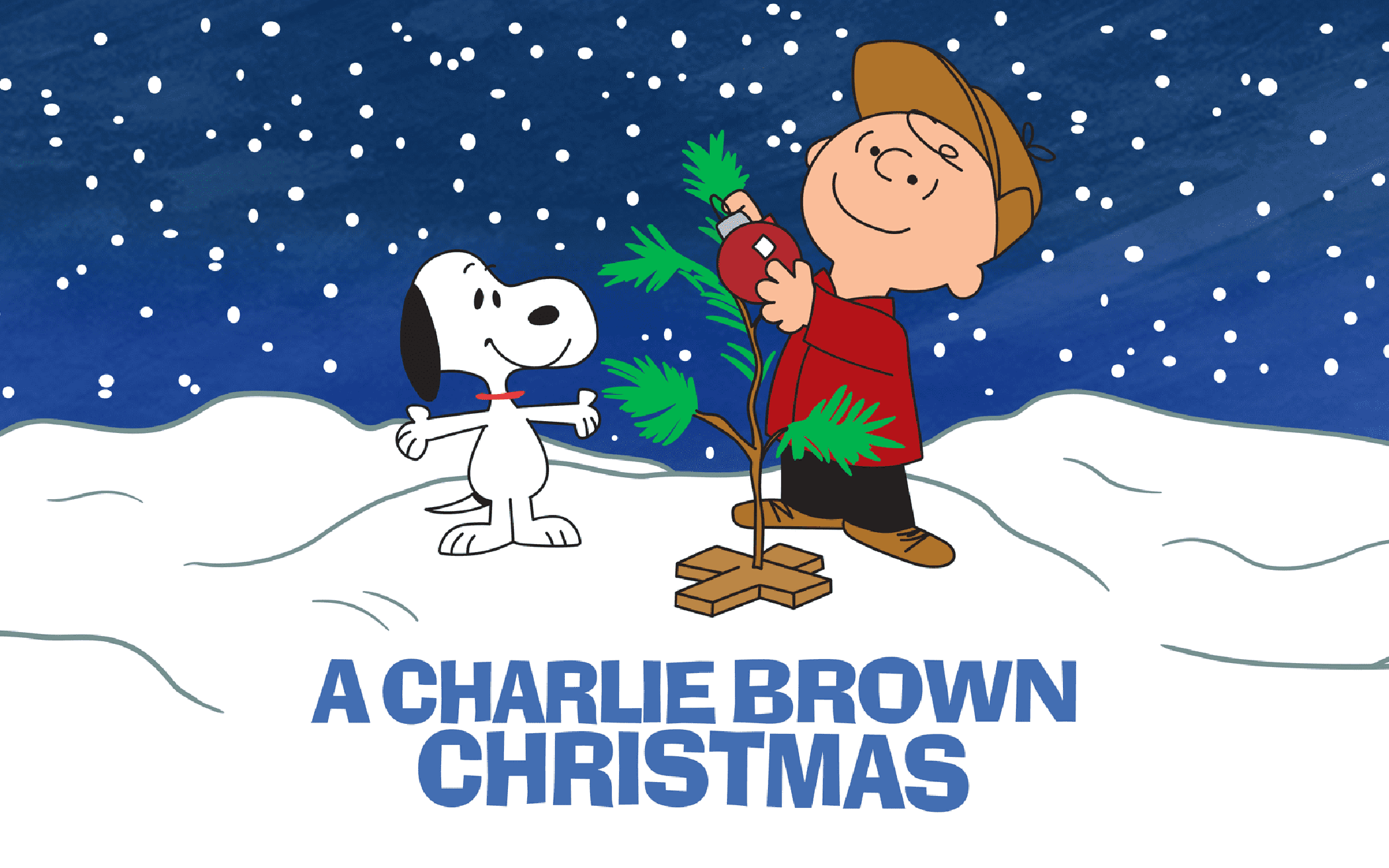

The 1965 animated special A Charlie Brown Christmas, developed by Charles M. Schulz, was predicted to be a flop.

The sponsor of the special, The Coca-Cola Company, was nervous. Reasons for a potential ratings disaster included bare-bones storytelling, a slow pace, no laugh track, religious references, children singing off key, a jazz soundtrack, and a main character (Charlie Brown) struggling with doubt and depression.

Charles Schulz, however, was determined to tell an honest and heartfelt story about the true meaning of Christmas.

With elbows firmly planted on a snow-covered stone wall, Charlie Brown says to Linus, “I think there must be something wrong with me, Linus. Christmas is coming, but I’m not happy. I don’t feel the way I’m supposed to feel. I just don’t understand Christmas, I guess. … I always end up feeling depressed.”

Feeling distraught and searching for answers, Charlie Brown finds his friend Lucy and sits down at her five-cent psychiatric help booth. After he expresses his feelings and tries to name his fears, Lucy is quick to give her advice. She concludes that the best medicine for Charlie’s depression is a good dose of activity. “How’d you like to be the director of our Christmas play?” she asks him.

Taking Lucy’s advice, Charlie heads to the auditorium, bumping into Sally and Snoopy on the way. They both offer him their thoughts about how to be happy at Christmas. Sally shares her wish list full of greedy demands for Santa. Snoopy enters a holiday competition and decks his doghouse with glitzy decorations. Both approaches to Christmas increase Charlie’s sadness.

Advent

Advent is a season of waiting, a season that anticipates the fulfillment of promises of a Savior. In his book Living the Liturgical Year, Bobby Gross says that our Advent waiting is powerfully formative because it has a dual nature: it invites us to both groan and sing. Both practices are needed to get us ready to receive the work God is doing throughout the biblical narrative, culminating in the most special gift ever given.

First, let’s consider the practice of Advent groaning.

After Charlie Brown shares with Linus about his depression, Linus responds, “Charlie Brown, you’re the only person I know who can take a wonderful season like Christmas and turn it into a problem.” But Charlie Brown has stumbled onto something essential about Advent. It’s not that Charlie’s looking for problems; rather, he’s searching and straining to see past the tinsel, past the lights, beyond the activities and activism to get a clearer view of the important and real. In the same way, in the weeks leading up to Christmas we are encouraged to take a long look at the brokenness all around us and inside of us. In Advent we stop, look, and weep over illness, poverty, chronic pain, estranged family relationships, abuse, injustice, political corruption, war, and the tragedy of another mass shooting. When we pause and peer through the sentimentality of the season, the clarity of sin we see evokes a deep sadness that stirs something inside—a longing in the depths of our spirit for intense goodness, beauty, healing, and wholeness.

But groaning for redemption is not the only practice Advent invites us into. Bobby Gross reminds us that practicing joy is equally powerful and important. To sing in Advent, however, is hard. To sing with real joy, we must get clear about what we want for Christmas.

Later in the story, Lucy identifies with Charlie Brown’s depression, and in a moment of surprising vulnerability says, “I know how you feel about all this Christmas business—getting depressed and all that. It happens to me every year. I never get what I really want. I always get a lot of stupid toys, or a bicycle, or clothes, or something like that.” Feeling understood for the first time, Charlie responds hopefully, “What is it you want?” To his dismay, however, Lucy says, “Real estate.”

Later, after some disastrous attempts at directing the Christmas play, Charlie Brown quietly leaves and goes searching for a stage decoration that will help focus the production. In a Christmas tree lot, he finds the only real tree among a dozen artificial ones and brings it to the theater. When his friends see it, they mock him, but Charlie intuitively knows he has found something that speaks of the true meaning of Christmas: a humble and weak tree, overlooked by most, disdained by others, but beautiful to those with eyes to see and hearts hungry for the real.

Almost every modern seasonal song tells us directly or indirectly what we should want for Christmas. Although Charlie is never asked what he wants, his heart’s intuition is fleshed out when Linus pauses in the middle of rehearsal and takes center stage. As the theater darkens, a spotlight illuminates Linus and his blanket as he recites the angelic message spoken to the shepherds in Luke 2: “Fear not, for behold, I bring you tidings of great joy that shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, which is Christ the Lord.”

The liturgical practices of groaning and singing are deeply biblical, described in passages such as 1 Thessalonians. Numerous verses from this short letter are often read during Advent because the situation to which they speak so closely mirrors our own. The author writes to a suffering church, waiting patiently in the middle of two promises. While they groan under the weight of sin, they are instructed to “rejoice always, pray continually, (and) give thanks in all circumstances” (1 Thess. 5:16-18). It can seem like a paradox to groan and rejoice at the same time, but it becomes possible when we get clear about what we want for Christmas and embrace with confidence the generosity of a God who “did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all—how will he not also, along with him, graciously give us all things?” (Rom. 8:32).

Hope Fulfilled

When A Charlie Brown Christmas aired Dec. 9, 1965, it was viewed by an impressive 45% of those watching television that night. Immediately, it received universal critical acclaim and became a yearly broadcast on network television until 2022—a remarkable 57-year run for a simple cartoon about a depressed boy straining to see past the superficial, searching for the true meaning of Christmas.

There is no right way to feel in the weeks leading up to Christmas. Like Charlie Brown, it’s normal to want to feel happy, but the Advent practice of groaning and rejoicing means that while we wait in pain between two wonderful promises, we can rest in the knowledge that God will be present with us this year and every year until the sadness of sin is wiped from our eyes and our divisions are done away with once and for all.

On that day of promises fulfilled, flowing from our hearts will be rivers of joy as we rise, join the triumph of the skies, and with angelic host proclaim, “Peace on earth and mercy mild—God and sinners reconciled!”

About the Author

Sam Gutierrez is the Associate Director at the Eugene Peterson Center for the Christian Imagination at Western Theological Seminary. More of his creative work can be found at printandpoem.com