[Updated Nov. 15, 2023]

Your guide to the history and development of Canadian ministry in the Christian Reformed Church.

Since early in 2020, staff and Council of Delegate members of the Christian Reformed Church wrestled anew with how the ministry of the CRC in the U.S. and in Canada should mesh together. It was the latest iteration of a conversation that has happened many times in the past 60 years.

How did we get here? It’s complicated.

In fact, to write this guide (first published in October 2021)The Banner went back through more than 100 years of synod records to help trace the origins of those wounds and frustrations. Why go back so far? Because the place of Canadian ministry in the denomination’s governance structure is inextricably tangled with governance structure discussions that go back decades before many Dutch immigrants landed on Canadian shores.

If you are one of the church members confused about what the CRC structure was, what has changed since 2020 and why—particularly in regard to Canada—you’ve come to the right place. An index is provided to allow readers to jump to specific turning points in the structure developments or jump immediately to the development they are most interested in. We put a glossary of terms at the end.

In many cases, the citations to synod materials are linked. If you follow those links, there is usually background and history for any noted report. Additional links to Banner articles are also included.

You’ll see that synod over the years appointed many, many study committees, far more than those mentioned in this guide. It adds up to a lot of people spending a lot of time on this seemingly intractable issue.

This guide doesn't cover everything the CRC has ever done about structure. For that, you’ll have to find your own way back through all the Agendas and Acts of annual synods. You can find documents up to 1999 in the Calvin University Hekman Library and more recent ones in CRC synod resources.

Though not exhaustive, we’ve done our best to make this guide helpful in understanding how our beloved Christian Reformed Church’s structure developed to where we are today—complete with a list of common terms, timeline, and diagrams, to help you keep all the players straight.

Gayla R. Postma

Retired News Editor of The Banner

Timeline

1864 The CRC’s administrative structure was pretty simple.

1902 A stated clerk is appointed.

1926 Canada was designated as a foreign mission field for the CRC. (Acts of Synod 1926, p. 84.)

1934 Synod assigned the few Canadian congregations to U.S. classes.

1950 Classis Ontario became the first Canadian classis in the CRC.

1957 Synod said yes to particular (regional) synods.

1960 But then again, no. Regional synod implementation was postponed.

1966/67 Synod approved establishing the Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada.

1971 CCRCC had no home in the CRC governance structure.

1980 Canadian ministry office opened.

1986 CCRCC still had no place in the structure.

1988 Joint Venture Agreements.

1990 Another structure proposal bit the dust. Still no on regional synods but more study.

1991 Synod appointed a CRC executive director of ministries.

1993 No (again) to regional synods, but CCRCC enhanced, study committee struck.

1994 Synodical Interim Committee became known as the Board of Trustees.

1995 Canadian ministry discussions heated up; Synod 1995 asked for further study to propose a new structure.

1996 Synod called for study of U.S. governance structure.

1997 A new place for Canadian ministry, Canadian Ministries Board replaced CCRCC.

1999 Proposed parallel U.S. structure rejected, Canadian ministries director resigned.

2000 A binational Board of Trustees was the solution.

2004 Changed focus for Canadian ministries director; the second Canadian ministries director resigned.

2011 Executive director released, structure conversations reemerged, and a task force appointed to study structure and culture in the CRC.

2012 Another director of Canadian ministries resigned.

2013 The task force studying structure tackled binationality; Canadians called a meeting about the future of Canadian ministry; joint venture agreements (again).

2014/15 Synod approved a proposal to replace the Board of Trustees with the Council of Delegates; new Canadian ministries director appointed.

2017 The Council of Delegates convened its inaugural meeting.

2019 Concerns over structure, again. Direction and control.

2020 Job descriptions changed, executive director resigned, new structures proposed.

And then COVID-19 struck.

May 2020 A possible way forward

October 2020 Proposed job descriptions received, new task force appointed.

November 2020 Structure plans hit a snag.

February 2021 Contextualized ministry.

May 2021 Evolving plan recommended: unified structure, with distinct Canadian Office.

Expanded joint ministry agreements.

How it all fits together

July 2021 Canadian ministries director dismissed, Canadian church members upset

2022 Synod will need to approve

UPDATE: After Synod 2022

Late 2022 and 2023

Terms and Definitions

Ecclesiastical Structure

Governance structure

Governance entities:

Synodical Committee, later named Synodical Interim Committee

Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada (CCRCC)

Board of Trustees

Canadian Ministries Board

Council of Delegates

Leadership positions

Stated clerk, later re-named general secretary

Executive Director of Ministries

Executive Director

Canadian Ministries Director

Task Force to Review Structure and Culture (TFRSC)

Ecclesiastical, Structure and Leadership team (ESL)

Structure and Leadership Task Force (SALT)

Legal Structure

Timeline

1864 The CRC’s administrative structure was pretty simple.

In the first decades of the Christian Reformed Church in North America, the establishing local churches organized themselves into classes and then the classes gathered together to become the general assembly called synod. A single committee of three ministers (called the synodical committee) took care of administrative functions.

1902 A stated clerk is appointed.

As we all know, work by committee isn’t all that efficient, so in 1902 a stated clerk was appointed to be primarily responsible for carrying out the tasks of the synodical committee. As the work became more complex, the stated clerk position became full time. Eventually this position was renamed “general secretary.”

1926 Canada was designated as a foreign mission field for the CRC. (Acts of Synod 1926, p. 84.)

1934 Synod assigned the few Canadian congregations to U.S. classes.

1950 Classis Ontario became the first Canadian classis in the CRC.

Classis Grand Rapids East requested this due to its ever-growing size—it had 43 congregations with more being planted all the time in Ontario during the post-war migration from the Netherlands (Acts of Synod 1950,p. 39). However, several Ontario congregations asked synod not to create a classis for them. The CRC in Kitchener, Ont., for example, said that a new classis would be financially weak since most of the churches were still receiving aid from the CRC fund for needy churches. It also said that a separate Classis Ontario would “retard the process of Americanization (of Canadian churches)” (Acts of Synod 1950, p. 458).

By 1953, there were four Canadian classes: Classis Ontario had been divided into three, and Classis Alberta was established (Acts of Synod 1953, p. 5).

1957 Synod said yes to particular (regional) synods.

In 1957, there were six classes in Canada, four in Ontario, and two in Alberta. In the U.S., large classes were dividing into smaller ones.

A report to Synod 1957 noted that the issue of regional synods had come up at synod 11 times, going back to 1894 (Agenda of Synod 1957, Supplement No. 17).

The frequent requests noted that synod gatherings were becoming so large as to be unwieldy and expensive. Synod agreed it should take the necessary steps (meaning, strike a committee) to establish particular synods (Acts of Synod 1957, Art. 100). There wasn’t anything connected specifically to Canadian churches at this time.

1960 But then again, no. Regional synod implementation was postponed.

Despite what Synod 1957 had said, Synod 1959 said keep studying the issue. After three years of discussion, Synod 1960 postponed implementation of particular synods because “the necessity, desirability, and feasibility of particular synods at this time have not been sufficiently demonstrated” (Acts of Synod 1960, p.78, italics original). As you’ll see, a plan for regional synods was never implemented.

After this, whenever the topic of regional synods came up, fears were expressed that a regional synod for Canadian churches would create sectionalism, rather than encourage U.S. and Canadian churches to work together.

1966/67 Synod approved establishing the Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada.

Synod 1966 noted that operating ministries in two different nations with different histories sometimes caused problems. The denomination was U.S.-oriented, thinking of itself as a U.S. denomination with congregations in Canada. Synod decided that the Canadian classes could take joint action on matters peculiar to Canada, such as contact with the government, spiritual care of men in the armed forces, and contact with other denominations (Acts of Synod 1966, Art. 74, II).

As a result, Synod 1967 enacted an agreement of cooperation with the classes of the Christian Reformed Church in Canada, which became known as the Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada (CCRCC) (Acts of Synod 1967, Art. 35, III). The Council’s first meeting took place in Winnipeg, Man.

1971 CCRCC had no home in the CRC governance structure.

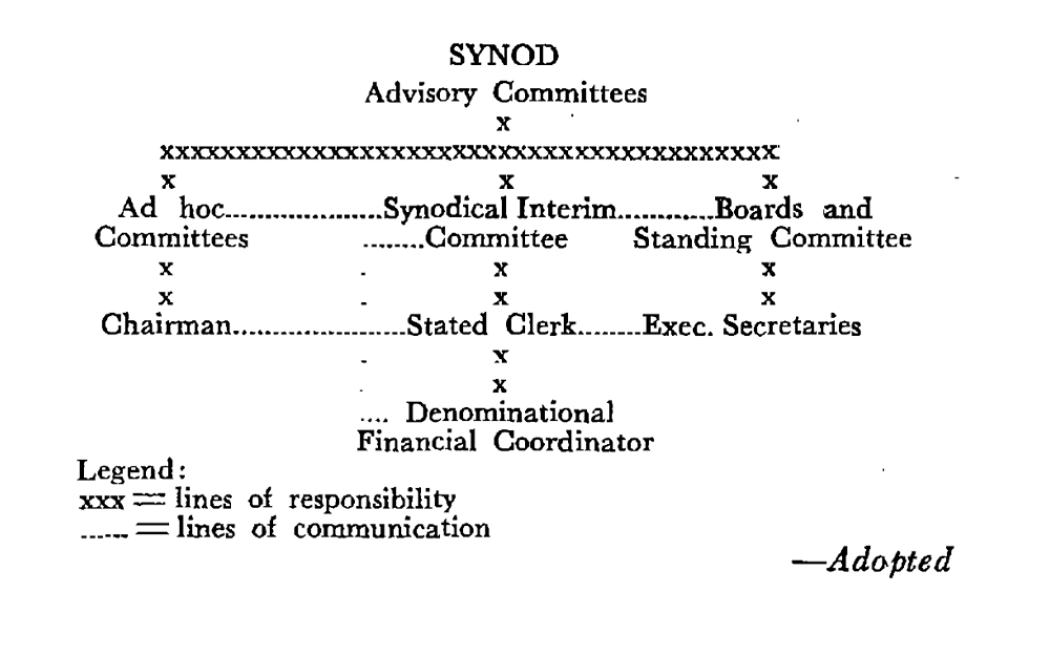

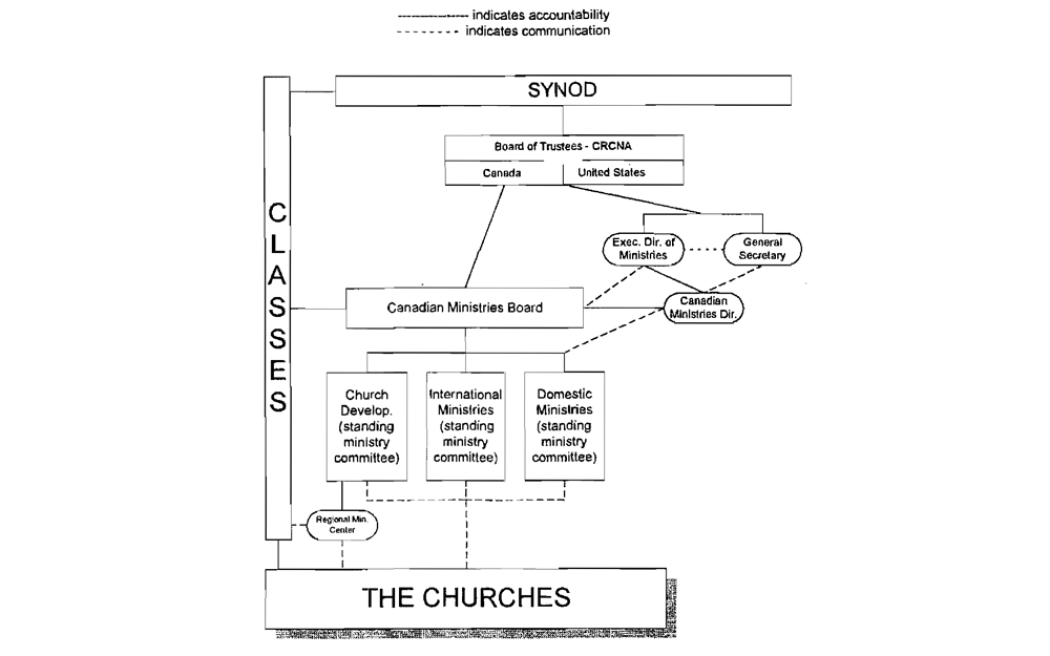

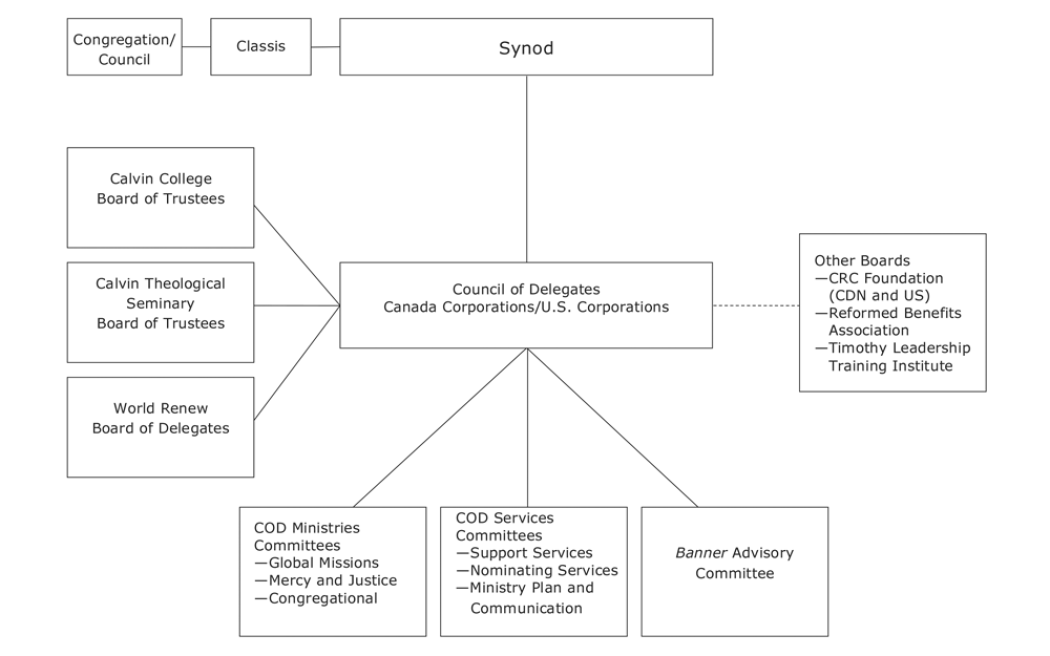

Synod 1971 made some changes to the denomination’s overall ministry structure to try to bring some coordination to the myriad agencies and committees that had grown up to advance the work of the kingdom of God (Acts of Synod 1971, Art. 87, I, C). The organizational chart looked like this:

Notice what is missing? There is no mention of ministries in Canada or the recently formed council. With no place in the larger church structure, the CCRCC had no official relationship with the U.S.-based agencies carrying out ministry in Canada.

1980 Canadian ministry office opened.

In 1980, the synod-approved Canadian office opened as a home for Canadian employees working for the denomination (Acts of Synod 1980, p. 411).

1986 CCRCC still had no place in the structure.

In the fall of 1986, the churches received a report that became known as Vision 21. The background to this report is long and we are not including it here because it wasn’t primarily about Canada. You can read it in the Agenda for Synod 1987, starting on p. 272.

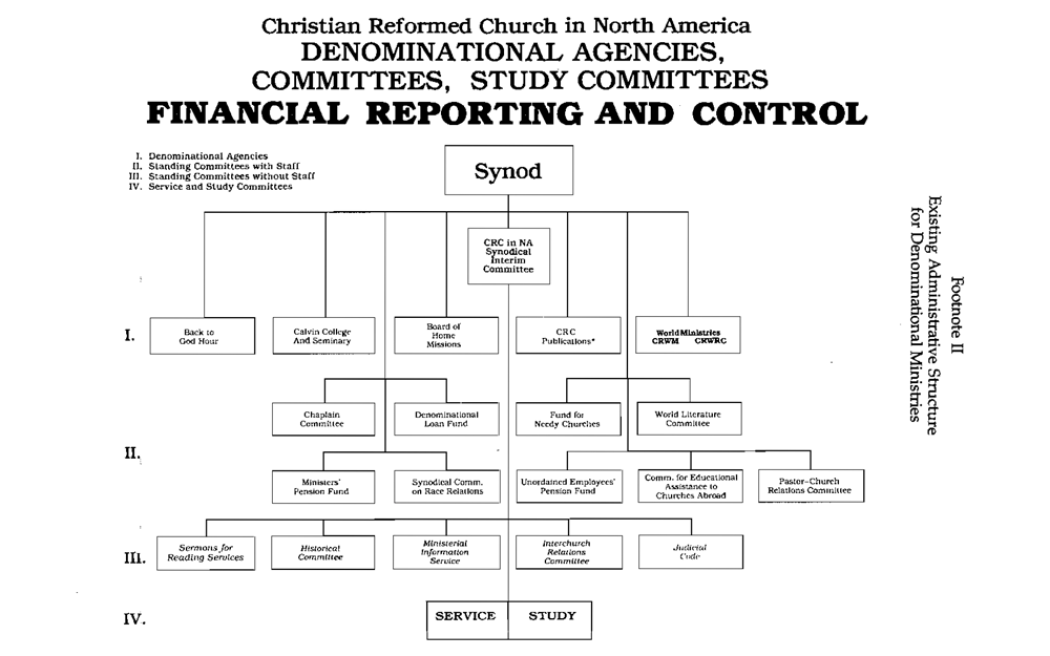

At the time the report was received, the denominational administrative structure looked like this (Agenda for Synod 1987, p. 292):

Notice that the Council of Christian Reformed churches in Canada still had no place.

The Vision 21 report recommended a structure that looked like this (Agenda for Synod 1987, p. 285):

You can see that proposed structure in more detail in the Agenda for Synod 1987, p. 310.

Almost all the Canadian classes and many of the American ones opposed this Vision 21 recommendation, as did most of the mission agencies, on the grounds that it would centralize too much power in a single governing body. Despite that, Synod 1987 (with two recorded negative votes) endorsed the general direction of the proposed model (Acts of Synod 1987, Art. 69) and mandated a new committee to recommend to Synod 1989 “modifications of denominational structures which are consistent with the intent and thrust of the report and which are responsive to the concerns expressed regarding the "Vision 21" report” (p. 597). Synod stipulated that the recommendations “shall include a plan for implementing these modifications.”

1988 Joint Venture Agreements

In 1988, the Agenda for Synod noted concern about compliance with Canada Revenue requirements. Canadian tax law requires that revenue from Canadian citizens be directed, controlled, and supervised by a legally incorporated Canadian board of directors.

The solution? Joint Venture Agreements. Remember this term, as it will come into play often as the Canadian CRCs seek to find their place in the denominational structure.

Joint Venture Agreements (now called Joint Ministry Agreements) are legal agreements whereby trustees from the two national corporations agree to function together in an international ministry. They were described as “the best means to meet the compliance requirements of

Revenue Canada” (Agenda for Synod 1988, p. 410).

Also note the words “direct” and “control.” You’ll see those words again, too.

1990 Another structure proposal bit the dust. Still ‘no’ on regional synods, but more study.

After receiving an extension, the committee appointed by Synod 1987 to recommend structure modifications in line with the Vision 21 report brought back its work as Report 27 (Agenda for Synod 1990, p. 331). The committee’s proposed structure had one less governance layer (a ministries board) than the previous model, and it now included an executive director (Agenda for Synod 1990, p. 350). Still no appearance of Canadian ministry as part of the structure.

Synod 1990 rejected it, saying, in part, “the proposed plan creates a layer of bureaucracy which impedes the grass-roots involvement of our members in denominational programs. The suggested array of existing agencies under seven operating committees forces change which these agencies perceive as detrimental to the continuity of their ministries and which would deprive several ministries of specialized staffing and expertise” (Acts of Synod 1990, Art. 98, C. 2). That argument had been used time and again over decades of structure studies, both before and after 1990. So despite one synod's requests for modifications, after study, a subsequent synod will just decide to leave things as they are.

How then to effect better coordination among the agencies? Synod 1990 beefed up the synodical interim committee with the authority to manage all the agencies, something previous synods had asked for but had not empowered the interim committee to do (Acts of Synod 1990, p. 673). And it approved the appointment of an executive director of denominational ministries (Acts of Synod 1990, p.674). This person was appointed by the next synod (see 1991 on the timeline).

In the midst of all the structure studies, the idea of regional synods kept popping up on synod agendas. They were considered a way for Canadians to have more autonomy over ministry in Canada. A study report to a later synod (“Regional Synods,” pp.247-274, Agenda for Synod 1993) described the issue: “Much of the ministry that lies close to the heart of the church (such as church planting, evangelism, the sending of missionaries, broadcast ministry, etc.) is administered by the agencies of synod, even when it occurs in Canada,” (Agenda for Synod 1993, p. 259). “At present,” the report said, “the Council (CCRCC) has no bearing on Christian Reformed agencies” (p. 263).

In any case, in 1990 synod agreed to have another look at regional synods on the grounds that it had not been studied since 1960 (Acts of Synod 1990, Art. 115, II, C,1).

1991 Synod appointed a CRC executive director of ministries.

Up to this point the leadership of CRC administration rested with one position: the general secretary (previously called the stated clerk). In 1991, synod added the position of CRC executive director of ministries. There previously had been an executive director of world ministries, to coordinate the work of both Christian Reformed World Missions (which became Resonate Global Mission) and CRWRC (World Renew). Synod decided the position should be expanded to supervise and coordinate the work of all the ministry agencies. That person would report to the synodical interim committee. The supervision of work included the agencies’ work in Canada (Acts of Synod 1991, Art. 99, I, D&E).

1993 No (again) to regional synods, but CCRCC enhanced, study committee struck.

The committee appointed in 1990 did not recommend regional synods (Acts of Synod 1993, Art. 87 C, 2). The study committee instead recommended an “enhanced Council in Canada” (Agenda for Synod 1992, p. 268). The CCRCC’s response? “The CCRCC did not ask for ‘enhanced standing’ but for greater effectiveness in its Canadian activities” (Agenda for Synod 1993, Overture 18, I, C, p. 292).

Nonetheless, Synod 1993 decided to keep the status quo and enhance the CCRCC by revising Church Order Article 44 to include that assemblies such as the CCRCC shall have direct access to synod (Acts of Synod 1993, Art. 87, C, 4). It also mandated another study committee to propose a more effective structure for ministry in Canada (Article 87, C, 7).

1994 Synodical Interim Committee became known as the Board of Trustees.

The CRC’s synodical interim committee (remember the initial, simple structure?) had functioned as trustees of the Christian Reformed church for a couple of decades. In 1994, the interim committee was renamed the Board of Trustees.

1995 Canadian ministry discussions heated up; Synod 1995 asked for further study to propose a new structure.

Issues around Canadian ministry started to reach a low boil. The committee appointed in 1993 named some of them, for example:

- mission opportunities were being missed, such as a Cuban mission field, something the Americans could not do because of American foreign policy;

- a broadcast ministry on the Vision television network (a broadcast network in Canada) could have been expanded but did not receive denominational funding;

- Canadians were paying twice for denominational programs—such as supporting Back to God Hour while paying for air time on Vision TV; they set up and paid for three ministries to Indigenous people in Canada, even while supporting CRC Home Missions and its Indian ministry in New Mexico (Agenda for Synod 1995, Structure for Ministry in Canada report, II, A).

And about that Canadian tax law: the committee noted that some agencies of the CRCNA created Canadian boards purely for formal purposes but that those boards were not autonomous in any meaningful way. “At present, then, our structures may perhaps satisfy the letter of Canadian law, but they do not satisfy its spirit or intent” (Structure for Ministry in Canada report, II, E).

As a result, Synod 1995 asked the CCRCC to reconstitute itself as the Board of Canadian Ministries that would be directly accountable to synod (Acts of Synod 1995, Art. 85, C, 4). It also decided to appoint a committee to serve the CCRCC in proposing a structure to coordinate and supervise the ministries of the CRC in Canada (Art. 89, C, 5).

1996 Synod called for study of U.S. governance structure.

Synod 1996 appointed a committee to study the structure for ministry in the U.S. as a complement to the Committee to Study Structure for Ministry in Canada (Acts of Synod 1996, Art. 65, I, B, 4).

1997 A new place for Canadian ministry, Canadian Ministries Board replaced CCRCC.

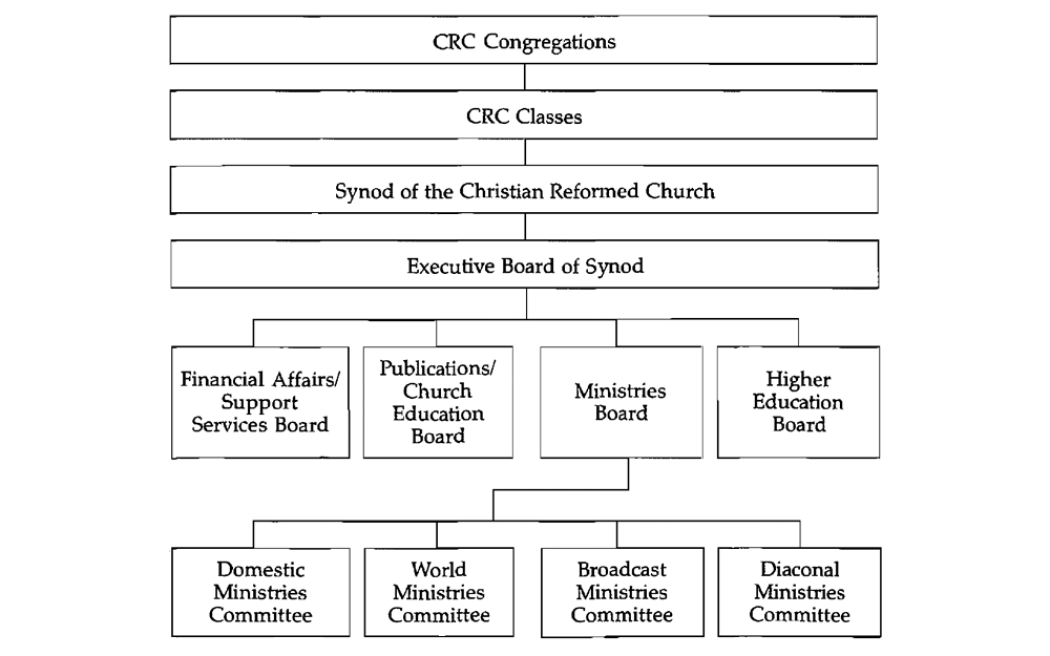

Synod 1997 adopted a new structure, one that included an official place for Canadian ministry (Acts of Synod 1997, Art. 40, C, 2). The Canadian Ministries Board, replacing the CCRCC, had authority over all ministries performed in Canada by Christian Reformed agencies. A Canadian ministries director was hired. The new structure looked like this: (Agenda for Synod 1997,p. 382 .)

1999 Proposed parallel U.S. structure rejected, Canadian ministries director resigned.

The effect of changes made in 1997 was somewhat undone in 1999 when synod rejected the plan for a parallel U.S. structure—it left some Canadians feeling pushed to the side.

What happened?

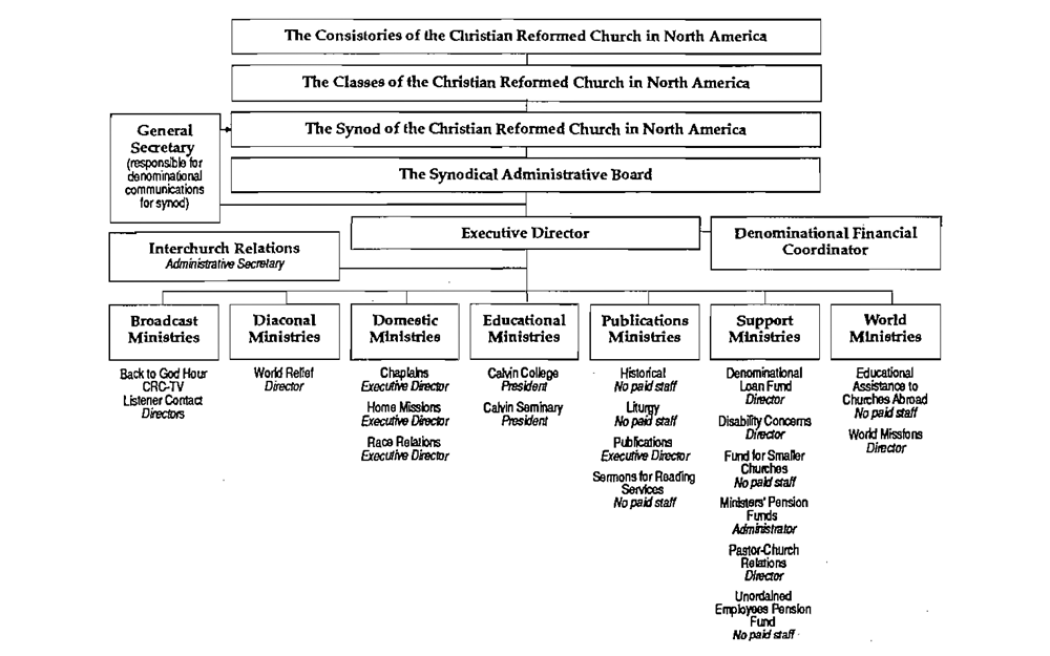

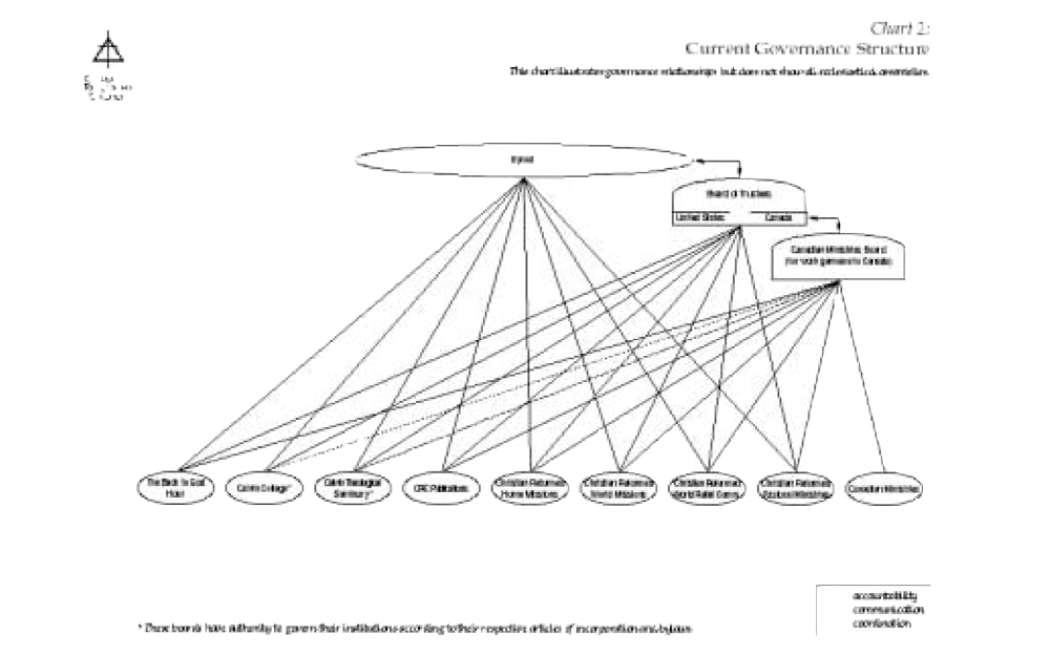

The committee appointed by Synod 1996 to look at the U.S. structure noted that there were extensive difficulties: too many governance layers approved by previous synods and too much dual accountability. The committee provided this chart (Agenda for Synod 1999, p. 324) to illustrate its point:

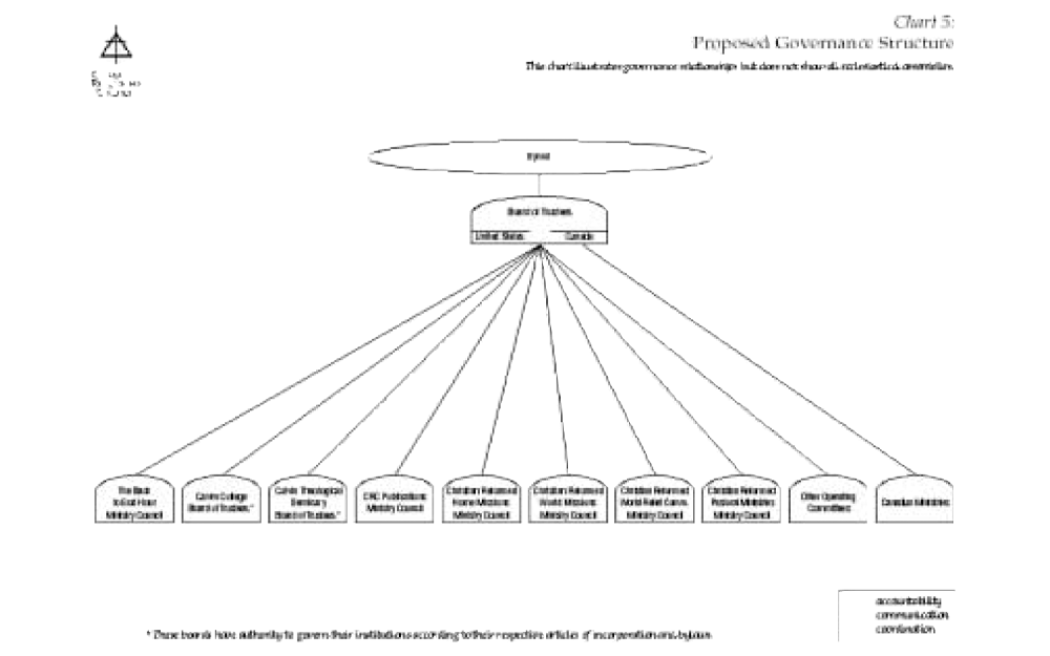

Instead, the committee proposed a much more streamlined model, shown in the next chart (Agenda for Synod 1999, p. 347). All ministries would report to synod through the Board of Trustees.

The board would be classically based. The Canadian Ministries Board, already a classically based board, would comprise the Canadian component of the CRC Board of Trustees. The Canadian ministries director would report to the Canadian Ministries Board.

Synod 1999 rejected the proposal. The main objection was the intent to make all the agency boards committees of the Board of Trustees, resulting in far too much centralization, the same argument used every time a more streamlined structure was proposed. Synod said that the structures already in place could achieve the goals of compliance and coordination among the agencies. (Acts of Synod 1999, Art. 44, C, 2.)

The 1999 decision left all the authority structures for the agencies intact, effectively removing the authority that had been placed with the Canadian Ministries Board in 1997. The Canadian Ministries Board, like the CCRCC before it, had no home. Ironically, the setting for this outcome—what many Canadians saw as a debacle—was Ancaster, Ont., the first synod ever hosted in Canada.

Synod 1999 told the Board of Trustees to solve it (Acts of Synod 1999, Art. 49, B. 6).

The first director of Canadian ministries resigned. He told The Banner, “The decision of Synod 1999 marginalized the mandate given to the Canadian Ministries Board by Synod 1997. I guess I’ve run out of energy and motivation to provide leadership to a team working in a context where the board is an anomaly in the church structure” (The Banner, Feb. 14, 2000).

2000 A binational Board of Trustees was the solution.

The Board of Trustees’ report to Synod 2000 noted that unless the CRC can find a mutually acceptable way to function binationally, a drift toward separation could not be ruled out (Agenda for Synod 2000, Board of Trustees report to synod, Appendix D). It also noted that due to the continual rejection of attempts to establish regional synods, “it is hard to measure the depth of feeling among Canadians about these repeated rebuffs by synod, but there is little doubt that these failed attempts have left an imprint on the Canadian church consciousness that surfaces again and again in conversations at classes and in private settings” (p. 55).

The solution would be parity on the Board of Trustees. Instead of a representative from each classis, the U.S. delegates would represent regions. That would create a board with an equal number of members from the U.S. and Canada. Both the Canadian and the Michigan corporations were given identical board committee structure to facilitate the oversight of the ministries of the whole church. The short-lived Canadian Ministries Board was absorbed into the newly constituted Board of Trustees. All the ministry agencies kept their own boards intact. (Acts of Synod 2000, Art. 23, C, 1.)

2004 Changed focus for Canadian ministries director; the second Canadian ministries director resigned.

With retirements of senior directors on the horizon, the Board of Trustees started studying the job descriptions and decided that instead of a general secretary and an executive director of ministries, the two positions should be merged into one position—executive director. It decided that some of the work of the general secretary could be shifted to the Canadian ministries director (Agenda for Synod 2004, Appendix I-1, III. C). The Board proposed a job description to that end (Agenda for Synod 2004, Appendix I-5).

An overture (request) to Synod 2004 noted that the proposed description for the Canadian ministries director was significantly different from the position description approved by Synod 1997 and that it could significantly affect the ministry of the CRC churches in Canada (Acts of Synod 2004, Ov. 25). A Canadian delegate to synod said that the new responsibilities would take the director’s time away from the work in the Canadian context.

The second Canadian ministries director resigned and returned to parish ministry. He told the Board of Trustees he didn’t hate the job. It was just not the job he signed on to do. “I thought I would get to direct something. That didn’t happen” (The Banner, November 2004). He told synod that he hoped the integrity of the position and Canadian ministry would be maintained.

The succession plan was adopted. The job descriptions of the executive director of ministries and the general secretary were merged. And a deputy director of denominational ministries, reporting to the executive director, would concentrate entirely on coordinating and planning a unified ministry by all the agencies. A new director of Canadian ministries (the third now) was hired with the job description that included some of the former general secretary duties.

Four years later, a report to synod would note that in the years following 2004 the Canadian ministries director “actually functions as a deputy to the executive director” (Agenda for Synod 2008, p. 81).

2011 Executive director released, structure conversations reemerged, and a task force appointed to study structure and culture in the CRC.

Canadian board members had experienced a decade of waning influence. In 2008 they agreed that Canadian ministry items would be rolled into the full board agenda. Within a year, the Canadian matters of business were reduced to a yearly election of officers, approval of the binational minutes for legal purposes, and receiving a brief report from the director of Canadian ministries—an agenda that was usually accomplished in about 10 minutes or less.

In 2010, the director of Canadian ministries requested time to address the whole board. The board said that all questions regarding Canadian matters would be deferred to the executive director.

In 2011, governance structure was again on synod’s agenda. It was precipitated in part by the departure of the CRC’s executive director and the subsequent resignation of the deputy director of ministries (Acts of Synod 2011, Board of Trustees Report I. E&F). Synod asked the interim executive director to appoint a task force (like a committee, but with a cooler name) to study the CRC’s structure and culture (Acts of Synod 2011, Art. 63, 3).

Related Banner coverage:

“CRC Executive Director Resigns,” The Banner, April 5, 2011.

“Director of Denominational Ministries Resigns,” The Banner, May 5, 2011.

“Synod Appoints Task Force to Review Church Structure,” The Banner,June 16, 2011.

“Editorial: Denominational Governance: Time to Get Back to Reformed Basics.” The Banner, April 27, 2011.

2012 Another director of Canadian ministries resigned.

As that structure and culture task force started its work, early in 2012, the interim executive director of the CRC told The Banner: “Binationality is a singularly significant issue for many Canadians, and a singularly confusing one to many Americans.” He noted that much of Canadian law is different from U.S. law and that Canadian politics are significantly different. And the relationship of the Canadian CRC to the government is different than it is in the U.S.

The president of the Canadian half of the Board of Trustees told The Banner that Canadian ministry is more than a few small non-U.S. programs. That view, she said, cheapens the perception of what the CRC is in Canada.

Related Banner article:

“Why Being a Binational Church is So Important,” The Banner, Feb. 3, 2012.

By autumn, the third director of Canadian ministries resigned. He told The Banner that the biggest challenge his successor would face was what he called the eternal questions of a binational denomination, where one part is larger than the other, with different histories and inclinations: “How does the Canadian part of the CRC maintain an effective national witness while being part of a united denomination? Does binationality require uniformity? How can national distinctiveness be celebrated without being perceived as a threat of division?”

Related Banner coverage:

“Director of Canadian Ministry Resigns,” The Banner, Sept. 7, 2012.

An interim Canadian ministries director was appointed.

2013 The task force studying structure tackled binationality; Canadians called a meeting about the future of Canadian ministry; joint venture agreements (again).

On the heels of this third resignation, Canadians gathered on short notice for the C3 Canadian Catalytic Conversation because of perceptions that the witness of the CRC in the Canadian context was dimming. Four representatives from each Canadian classis traveled to Toronto for the informal meeting.

Related Banner coverage:

“January Conference to Address Canadian Role in Binational Church,” The Banner, Nov. 20, 2012.

One of the statements that came out of that gathering said, “While supporting a binational church, Canadians need a unique voice to respond to a national context that is bilingual, secular, multicultural, and with different political systems that deeply impact ministries in public justice, health, education, and ecumenical relations.”

Related Banner coverage:

“Canadian Forum Causes Both Appreciation and Frustration,” The Banner, Jan. 17, 2013.

That year, when a Canadian classis asked that Canadian members of the Board of Trustees be allowed to conduct separate meetings, it was determined that there was no need—board members were already meeting informally.

Related Banner coverage:

“Canadian Concerns Taken Care of, Synod Says,” The Banner June 11, 2013.

Meanwhile, the task force for reviewing structure and culture outlined some of the concerns about binationality that always come up when it is discussed: fear of separation, fear that one nation dominates the other, and management centralization (Agenda for Synod 2013, Task Force Reviewing Structure and Culture, IV, E).

The task force noted areas where the Canadian and American contexts differ significantly. For example:

- Immigration trends differ substantively. Immigration to the United States is dominated by working-class Hispanics and Latinos who have a Christian background (mostly Roman Catholic); while immigration to Canada is dominated by middle-class Asians and Africans who are largely non-Christian.

- Canadian aboriginal ministries (these ministries have since been renamed Indigenous Ministry) were established to work with people who are affected by how Canada treats its First Peoples, distinct from CRC ministry with Native Americans in the United States.

- The Canadian health care system operates differently than the U.S. health care system, affecting the delivery of chaplaincy care. Prisons and the correctional system in Canada are managed differently than in the United States, with implications for prison chaplaincy. While the U.S. and Canadian military cooperate in some conflict zones, understanding how each approaches chaplaincy is essential to the process of developing chaplaincies within the military. (Agenda for Synod 2013, Task Force Reviewing Structure and Culture, IV, G.)

“The potential need for differentiation to effectively respond in a national context should be considered in relation to every ministry rather than assuming general commonality with a few exceptions for so-called ‘unique’ national ministries,” the task force wrote.

The Board of Trustees told Synod 2013 it supported an option that would give the director of Canadian ministries full leadership responsibility for strategic planning in Canada, including opportunities for dealing with the financial challenges of implementing such a plan (Acts of Synod 2013, Board of Trustees supplementary report, Appendix A, p. 456).

Synod 2013 also noted that Canadian legal counsel prepared draft joint venture agreements for use by the agencies of the CRC that were approved by the Board of Trustees in May of that year (Acts of Synod 2013, Board of Trustees supplementary report, I. F, italics original).

2014/15 Synod approved a proposal to replace the Board of Trustees with the Council of Delegates; new Canadian ministries director appointed.

After several years with an interim director, Synod 2014 welcomed a new Canadian ministries director.

Related Banner coverage:

“Roorda Ready to Serve Canadian Churches,” The Banner, June 16, 2014.

Synod 2015 approved the plan, proposed in 2014, to dissolve the Board of Trustees and form a Council of Delegates (Acts of Synod 2015, Art. 74, C, 1).

Some of its particulars:

- The Council would have one representative from each classis, with Canadians making up about one third of the body. Its executive committee would include an equal number of Americans and Canadians.

- Canadian and U.S. delegates would meet separately on a regular basis to intentionally identify contextual factors and priorities to be considered in developing and implementing ministry plans.

- Canadian delegates would comprise the Canada Corporation, ensuring fulfillment of all components in the mandate from synod and compliance with all legal obligations as required by the Canada Revenue Agency (Agenda for Synod 2015, Task Force Reviewing Structure and Culture report, Appendix C, II, C).

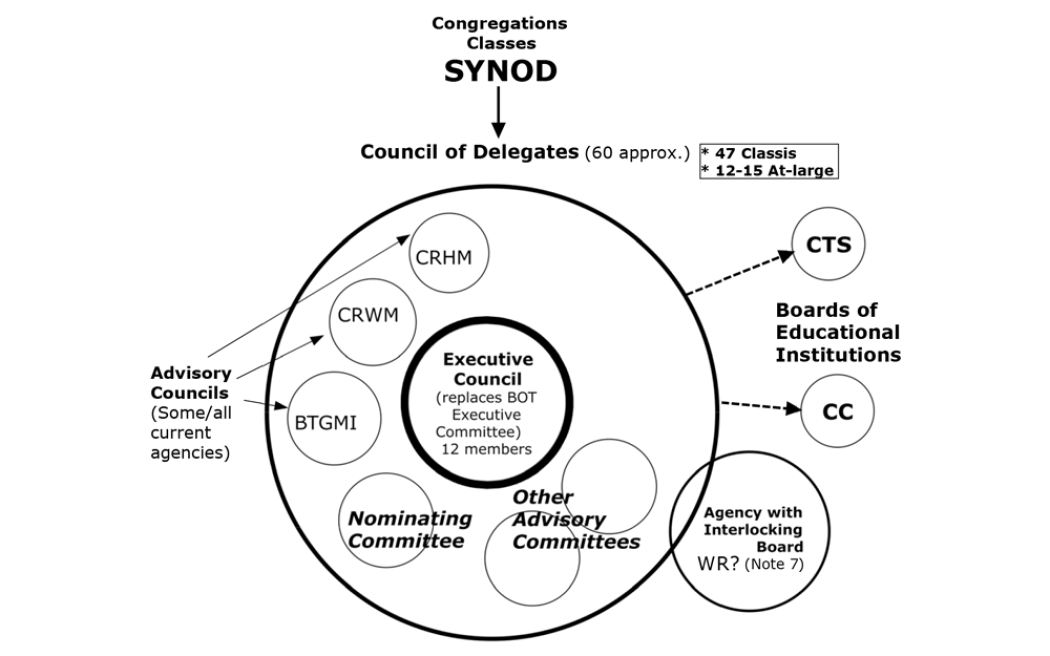

This is how Synod 2014 pictured the Council (Agenda for Synod 2014, p. 380):

The boards of Calvin University (then College), Calvin Theological Seminary, and World Renew were left intact. All other boards became committees of the Council.

2017 The Council of Delegates convened its inaugural meeting.

The Agenda for Synod 2017 had a slightly more detailed view of the structure (p.128):

The newly created Council met for the first time in October 2017.

Related Banner coverage:

“Council of Delegates Holds Inaugural Meeting,” The Banner, Oct. 13, 2017.

2019 Concerns over structure, again. Direction and control.

Satisfaction with the new structure was short-lived. A query from some Canadian churches about how well the Canadian legal tax requirements were being met led the Canadian delegates on the Council to seek a legal opinion. The primary issue was the requirement that direction and control of resources obtained in Canada stay in Canada. (Remember that from 1988?) Ceding control to entities (synod and the Council of Delegates) that are 75% American runs afoul of Canadian legislation. (Agenda for Synod 2020, Council of Delegates report I, D.)

As a result, the Canada corporation made changes to its structure, appointing an executive director-Canada (interim) and appointing several staff as directors of the various mission agencies in Canada on an interim basis. A letter to the CRC congregations noted that the changes affected only legal and corporate structure and did not affect the shared theology as the binational Christian Reformed Church in North America.

Related Banner coverage:

“Governance Restructuring Gives CRCNA in Canada More Ministry Control,” The Banner, Feb. 22, 2020.

2020 Job descriptions changed; executive director resigned; new structures proposed.

In response to the Canadian changes in structure, the president of the Council of Delegates said in February 2020 that 22 U.S. job descriptions had to be changed. People who were previously directors of ministries for the whole denomination were now directors of those ministries only in the U.S.

One of those whose job description was changed was the executive director. He resigned during the Council’s February meeting. In its report to synod, the Council noted that his resignation was due to structural changes in the relationship between Canada and the USA and anticipated changes to the executive director’s job description. (Agenda for Synod 2020, Council of Delegates report, II, A, 1.)

Related Banner coverage:

“CRCNA Executive Director Resigns,” Feb. 20, 2020).

The Council reported to Synod 2020 that a group of Council members and senior staff were addressing the ecclesiastical, structural, and legal implications of the changes. That team—dubbed the ESL task force—was to propose a way forward (Agenda for Synod 2020, Council of Delegates report, I. D.).

And then COVID-19 struck.

Complicating everything, the COVID-19 pandemic meant that the Council could not meet in person. All meetings took place via video technology, and two synods in a row were canceled. Council had to act for Synod 2020 and 2021 in its role as the synod interim committee. If synod had taken place in 2020 or in 2021, the congregations and classes could have weighed in using the normal process of overtures and communications. Without a synod, there really was no appropriate place for the overtures to go, leaving everyone waiting until a synod can meet again.

May 2020 A possible way forward

Based on the ESL task force’s report, the Council adopted three overarching principles:

- Leadership of the CRCNA must be done through an independent executive director in each country. Together they would monitor the joint ministry agreements for shared programs.

- There must be an ecclesiastical officer who can shepherd the denomination forward in a way that fosters unity across the border.

- The plan should be revisited in three years (Council of Delegates supplementary report contained in the Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2020, Council of Delegates Supplement, I. G.).

Related Banner coverage:

“Still Bumps in the Road for CRC’s Restructuring,” The Banner, May 8, 2020.

“Governance Restructure Subject of Recent Canada Corporation Meeting,” The Banner, July 24, 2020.

October 2020 Proposed job descriptions received, new task force appointed.

The Council received job descriptions for the proposed two executive directors and the proposed ecclesiastical officer. The U.S. and the Canadian corporations endorsed their nation-specific position descriptions.

The Council subsequently appointed a structural and leadership task force (known as SALT) to ensure that the three reports/position descriptions were complete and compatible, and address other relevant ecclesiastical considerations. This task force’s mandate also included obtaining legal reviews from Canadian and U.S. legal counsel. (Agenda for Synod 2021, Council of Delegates report, II. A, 8.)

November 2020 Structure plans hit a snag.

Obtaining legal reviews resulted in two different legal approaches. Both opinions agreed that Canada corporation had to be in compliance with Canadian tax law. Where they differed was in how to accomplish that. One saw the solution as each corporation having an executive director with an extensive Joint Ministry Agreement process to clarify the working relationship. The other said the solution could be managed with a very simple JMA process and less structural change.

A way between the two approaches had to be found. The Council called a December meeting, which was convened as a closed session and was described as an open time of listening to each other.

Related Banner coverage:

“Extra Meeting of the CRC’s Council of Delegates Intended as ‘Special Listening Session,’” The Banner, Dec. 17, 2020.

The deadline for the SALT report, originally scheduled for February, was extended to May 2021.

February 2021 Contextualized ministry.

At the February 2021 meeting of the Council, one American delegate noted that while the presenting issue for structure change was tax compliance, there is a lot more history involved in the discussion of binationality. “There is a history of not living into decisions we’ve made. There’s a historic wound and frustrations surrounding that. There is also a contemporary desire for contextualized ministry.”

A letter sent to the Canadian congregations from the Canada corporation the previous year had said “since we are in need of restructuring moving into 2021, it is best to consider how ... for the most effective contextual approach to ministry in Canada.” So a team—the Canadian restructure team—had been working on that and produced a contextualized ministry plan with the help of a consultant. In February, Canadian delegates to the council put the brakes on that work until the joint work of SALT could be completed.

Related Banner coverage:

“Governance Restructure Causing Confusion, Angst,” The Banner, Feb. 22, 2021.

May 2021 Evolving plan recommended: unified structure, with distinct Canadian Office.

The much-anticipated SALT report was sent to the Council just days before its May 2021 meeting. (The entire SALT report is in the Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, Council of Delegates report, Appendix A.)

It proposed some changes to the trajectory that had been set in October. The initial plan had executive directors in each country. As SALT deliberated, it determined the dual structure wasn’t the right approach.

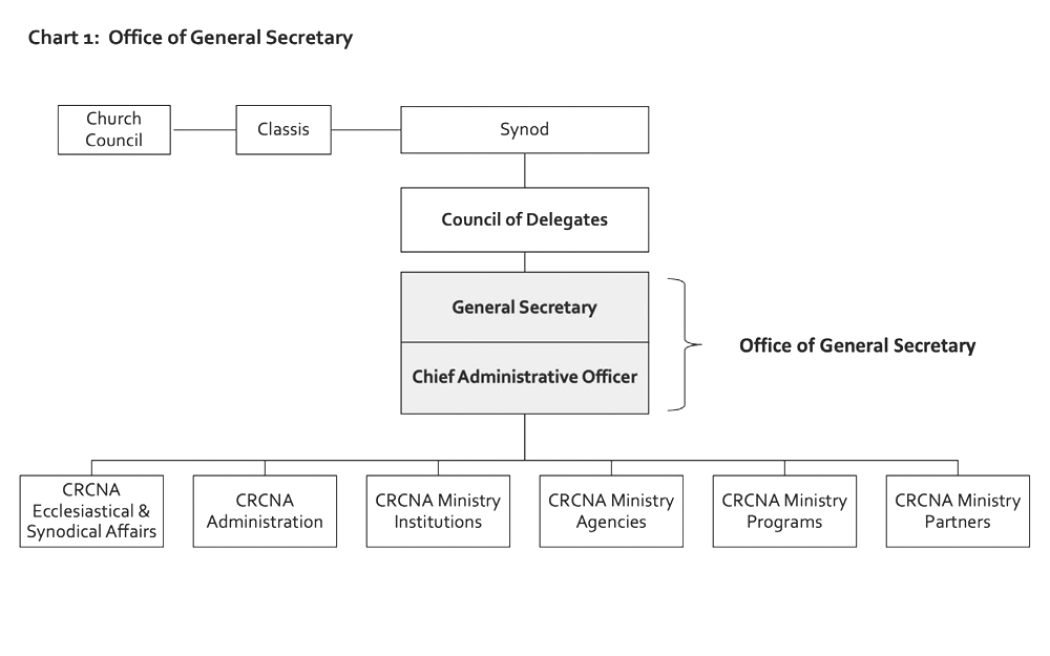

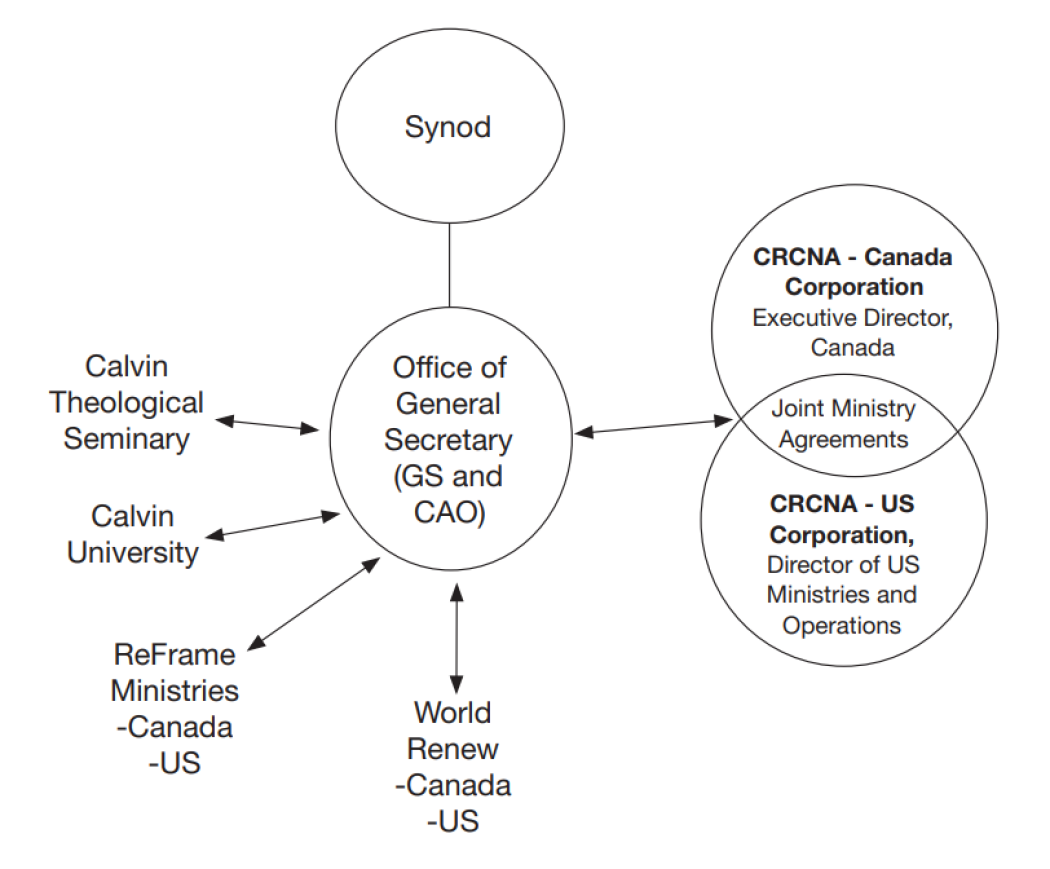

In the SALT report, the previously proposed ecclesiastical officer became the “office of the general secretary” comprising two positions—general secretary and chief administrative officer. An executive-director Canada was still in the mix. The office of general secretary “will be responsible and accountable to the Council of Delegates to guide and direct the entire CRCNA organization,” the report said (Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, p.525).

(Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, p. 525)

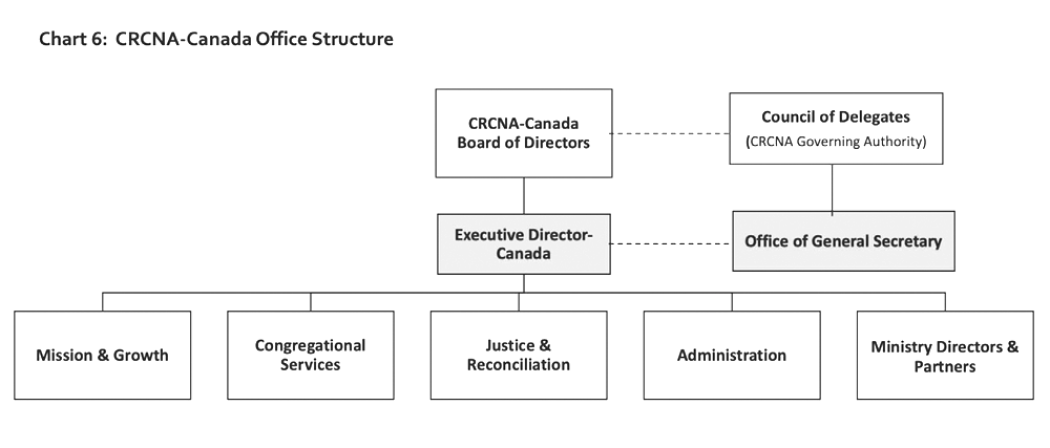

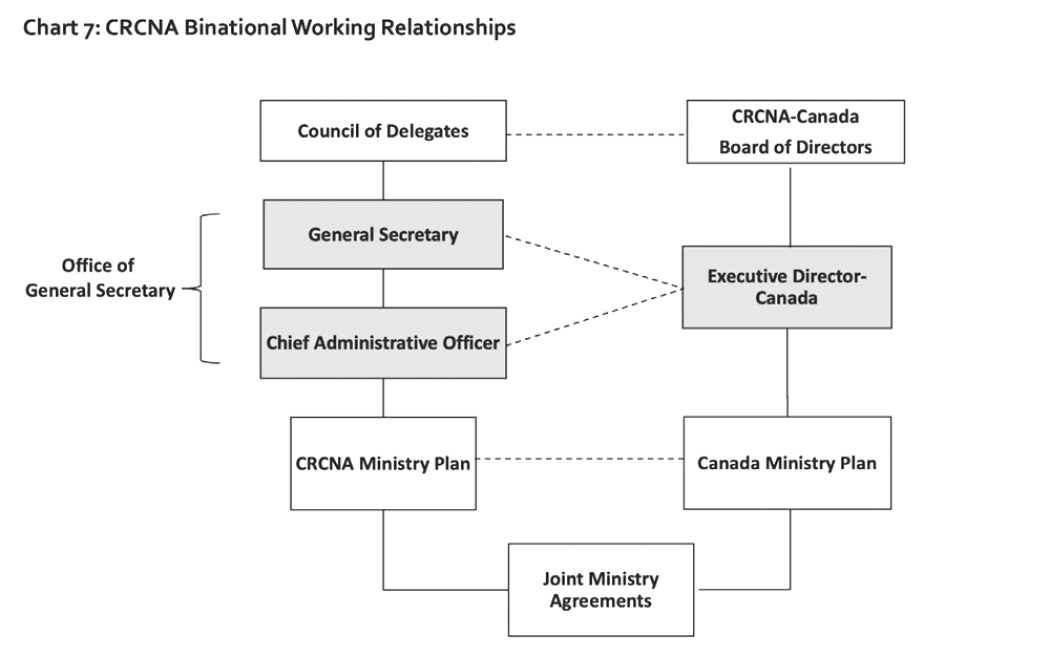

The executive director-Canada will oversee and direct the CRC ministry leaders, partners, and programs in Canada. “The purpose of the Canadian Office is not to mirror the U.S. Office of the CRCNA organization,” the SALT report said. “Instead, it is to implement the CRCNA Ministry Plan through the use of Joint Ministry Agreements in a manner that recognizes the ministry needs of Canadian churches and that of their social and cultural context” (Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, p. 535). A chart from the SALT report illustrates these relationships:

(Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, p. 534)

The SALT report drew attention to the use of dotted lines to describe how boards and leaders need to work as partners to accomplish a shared mission. “These relationships are not defined by control or direction,” it said (p. 534, italics original).

When asked why the proposed executive director-U.S. was dropped in the new proposal, the delegate that chaired the SALT team said the goal was not parity, but ministry need.

Expanded joint ministry agreements.

The SALT report recommended an expanded joint ministry agreement process to clarify the governance and administrative responsibilities between the U.S. and Canada. A new task force (yes, another one) appointed by the Council is overseeing this.

When the new structure is in place, the process of developing and overseeing joint ministry agreements will be managed by the office of general secretary and the leaders of the denominational agencies.

In addition, a new office of governance will help board members to exercise their fiduciary and governing responsibilities; oversee the governance framework and make recommendations for improvements; and assist with compliance with tax law in both countries.

How it all fits together

(Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council of Delegates 2021, p. 535)

When the Council reviewed the SALT report, several Canadian delegates objected to the elimination of a clear dual structure. They wanted the proposal tabled. The Canada Corporation drafted a communication to the full Council expressing its concerns and opposed the report’s adoption. Although the SALT report included a separate Canadian office with its own “Canada Ministry Plan,” some of the Canadian delegates couldn’t see how partnership was possible without a parallel dual structure. One Canadian delegate told the Council, “The main point is partnership. And that is what I am missing in the SALT report. We have had these discussions for 30 years on the Canadian side of the denomination. We want to maintain unity. We need that new culture of partnership.”

The Council voted against tabling the proposal.

The Canadian ministries director left mid-meeting.

The Council adopted the proposal.

Related Banner coverage:

“New Leadership Structure Recommended Amid Much Disagreement,” The Banner, May 14, 2021.

“New CRCNA Leadership Structure: What Is It?” The Banner, May 14, 2021.

July 2021 Canadian ministries director dismissed, Canadian church members upset.

Following his abrupt departure from the May Council meeting, the Canadian ministries director took a short leave of absence. In July he was dismissed from his position. The president of the Canada corporation said that the board and the former Canadian ministries director agreed on the end goals of a contextualized ministry in Canada, compliance with Canadian tax law, and remaining one denomination. But how to get there became a stumbling block in the relationship.

A letter signed by 86 ministry leaders in Canada asked the board for clarification.

Related Banner coverage:

“CRC in Canada Parts Ways with Canadian Ministries Director,” The Banner, July 6, 2021.

“Roorda Dismissal Prompts Questions; Board Says End Vision is Same,” The Banner, July 23, 2021.

At its July 2021 meeting, the Canada corporation decided to open dialogue with that group and they put the on-hold report about contextualized Canadian ministry (remember, from February) into the hands of staff and the committee implementing the SALT report recommendations.

Related Banner coverage:

“Canadian Board Supports Restructuring, Wants More Canadians on Council,” The Banner, July 30, 2021.

2022 Synod will need to approve.

Where are we now? [October 2021]

After being vetted by lawyers and the Canada Revenue Agency, and soliciting feedback from churches and classes, the Council will send the proposed model to Synod 2022 for final approval.

In preparation for that, the Council executive is in the midst of creating mandates and search teams for each leadership position, and a steering committee is coordinating the completion of the joint ministry agreements.

UPDATE: After Synod 2022

The CRCNA Canada Corporation announced the appointment of a two-year transitional executive director in April 2022.

Synod 2022 adopted the structure changes in the Structure and Leadership Taskforce report (Acts of Synod 2022, pp. 928-930), and it interviewed and approved the Council of Delegates' proposed candidate for general secretary. There was no candidate presented for the role of chief administrative officer; instead, synod granted authority to the Council of Delegates to appoint a CAO and all senior-level staff within the Office of General Secretary (Acts of Synod 2022, p.930). An interim administrative officer was named at the end of June.

Related Banner coverage:

“Canadians Appoint Transitional Executive Director,” The Banner, April 28, 2022

“Synod 2022 Adopts New Governance Structure,” The Banner, June 16, 2022

“Synod 2022 Appoints New General Secretary, Asks Tough Questions,” The Banner, June 16, 2022

“CRC Names Interim Chief Administrative Officer,” The Banner, July 1, 2022

Synod depicted the interactions between the Office of General Secretary and the CRCNA's various legal corporations with a diagram of interconnected circles (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 928).

(Acts of Synod 2022, p. 928)

Like many synods before it, Synod 2022 attempted to clarify the place of Canada within the Christian Reformed Church in North America, this time laying out the relationship in an Ecclesiastical Mandate Letter (Acts of Synod 2022, pp. 718-721).

"As an ecclesiastical partner, CRCNA Canada is responsible," the letter says, to "transact those matters assigned by Synod as it seeks to further its mission and ministry in Canada ... contribute to the formation, development, implementation, and evaluation of the CRCNA Ministry Plan ... (and) establish and operate the Canada Office of the CRCNA ... (which) will:

- Manage the affairs of CRCNA Canada as a registered charity,

- Develop, contextualize, implement, and evaluate the CRCNA Ministry Plan to ensure ministry is culturally appropriate,

- Collaborate with local churches and classes to identify and address ministry priorities,

- Develop and manage the Joint Ministry Agreements with CRCNA organizations and ministry partners,

- Represent and maintain ecumenical and ecclesiastical relationships in Canada in conjunction with the General Secretary" (Acts of Synod 2022, pp. 720-721).

Starting off on a new foot (again) on binationality, Synod 2022 didn't ignore the painful journey to this point. In background to the recommendations it adopted, synod said, "In all of this we highly value binationality and the continued unity of our denomination. While we recognize that heartache, frustration, and pain have been felt along the way, we are hopeful that this new structure and leadership will place the CRCNA in a strong position to move forward and confidently share the gospel" (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 928).

Synod 2022 endorsed the formation of a separate legal entity to house the Office of General Secretary—thus separating the ecclesiastical office from any other corporations of the CRCNA. The Council of Delegates is tasked with determining a name for this new ecclesiastical corporation and approving its final bylaws (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 929). (Draft bylaws were included in the Acts of Synod 2022, Appendix B2, starting on p. 729.)

Synod 2022 also wanted clarity on how the denomination uses "the terms agency, board, office, ministry, and similar names for CRCNA entities." It gave the Office of General Secretary the job to review and clarify these terms "in order to provide clarity in communicating about the roles of these entities" (Acts of Synod 2022, p. 930).

Late 2022 and 2023

Clarified terms now include Canada Ministry Board and U.S. Ministry Board (formerly referred to as the Canada and U.S. Corporations). The Council of Delegates is concerned with “ecclesiastical governance” and the ministry boards are concerned with “organizational governance.”

A chief administrative officer is hired for the Office of General Secretary, but the establishment of the separate legal entity to house the Office of General Secretary is not yet complete.

The U.S. Ministry Board hired its own executive, a position known as director of U.S. ministry operations.

Synod 2023 established Thrive as a new agency of the CRCNA. It encompasses nine former ministries and is led by a U.S. and a Canadian director.

The Canada Ministry Board says there is expectation from the Canadian classes that Canada-wide conversations would continue and it plans a January 2024 discussion on church planting.

Between July and September a grassroots group called “Towards CRC Canada” forms and after sending a letter to the Canada Ministry Board, begins to engage Canadian CRC members about discerning and planning for “an independent CRC in Canada.”

Related Banner coverage:

“Internal Candidates Appointed as CRC’s Synodical Services Director, Chief Administrative Officer,” The Banner, Nov. 17, 2022

“U.S. Ministry Board Hires Director of U.S. Ministry Operations,” The Banner, May 9, 2023

“Synod 2023 Dissolves Mandates of Former Offices, Other Significant Acts,” The Banner, June 19, 2023

“Council of Delegates Makes Decisions, Boards Take Actions on Canada, U.S. Issues,” The Banner, Oct. 18, 2023

Terms and Definitions

Have you gotten lost? That’s what this list is here for—don’t worry, there’s no test. CRC-specific words, phrases, and entities are described here, along with the acronyms that sometimes stand in for them. (Though in the guide we have tried to keep the acronym alphabet soup to a minimum.)

There are three kinds of structure within the CRC: ecclesiastical, governance, and legal.

Ecclesiastical Structure

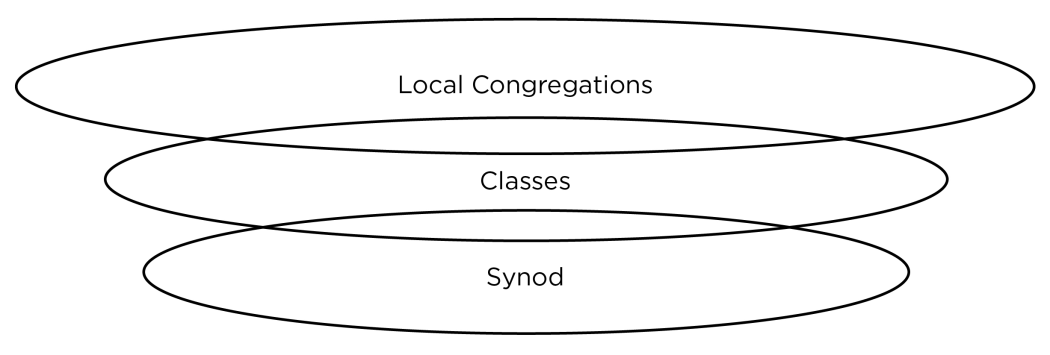

The CRC has an ecclesiastical (the word derives from the Greek ekklesia, “church”) structure, shown here.

Local churches: There are about 1,100 congregations in the CRC. In the CRC’s polity, original authority for all church matters is vested in the councils (sometimes called consistories) of the local churches. Councils are made up of the officebearers (deacons, elders, pastors) who lead and shepherd their congregations.

- Classis (classes, plural): Congregations are gathered into regional, mostly geographical, groups called classes. Two or three officebearers from the local churches are delegated to classis, where they encourage and support each others’ ministries, create ministries they can do together, and ensure that congregations in the classis are complying with the CRC’s Church Order. In 2021 there are 49 classes in the denomination. The authority of the classis is derived from the congregations.

- Synod: Once a year each classis sends four officebearers to an annual meeting of the denomination—synod. The gathering discusses the denomination’s ministries, decides on changes to Church Order, and calls for studies into matters of importance to the member churches.The varied ministries that report to synod were all created by synods over the years. Synod derives its authority from the classes, making it the broadest authority in the CRC. The actions taken by synod are recorded in Acts of Synod for each year. (As mentioned in the introduction to this guide, you can find documents up to 1999 in the Calvin University Hekman Library and more recent ones in CRC synod resources.)

- The Church Order: This is basically the book of rules governing the ecclesiastical life of the CRC. The rules that the congregations and the classes have agreed upon over many years, a covenant they have made with each other. (This is also available from synod resources.)

This ecclesiastical structure has remained unchanged since 1865 when a second classis joined the first to become the general assembly we now call synod.

Governance structure

The CRC also has a governance structure. That is how all the various ministry agencies and educational institutions of the denomination are structured administratively, just as has been shown in the various organizational charts throughout this guide. This is what has been tinkered with and overhauled for more than 60 years.

Governance entities:

Synodical Committee, later named Synodical Interim Committee

- As far back as 1864, the denomination created a committee of three ministers to deal with correspondence, implement synodical decisions, and give advice to classes.

Council of Christian Reformed Churches in Canada (CCRCC)

- CCRCC was established in 1966 to start and supervise ministries specific to Canada. Because this name is so long, in the guide we’ve referred to it as CCRCC.

Board of Trustees

- The synodical interim committee became known as the Board of Trustees in the early 1990s. That governance body was the precursor to the CRC’s Council of Delegates.

Canadian Ministries Board

- The Canadian Ministries Board was the successor of the CCRCC, formed in 1997. It was dissolved in 2000 when its functions were absorbed by the CRC’s Board of Trustees.

Council of Delegates

- A council made up of one delegate for each of the CRC’s classes and up to 10 at-large delegates, this is the current governing board of the CRC.

Leadership positions

Stated clerk, later renamed general secretary

- First appointed in 1902, the stated clerk was primarily responsible for carrying out the tasks of the synodical committee. As the work of the synodical committee and the stated clerk became more complex, the stated clerk position became full time. In 1990 the position was renamed general secretary. In 2004, this position was absorbed into that of executive director.

Executive director of ministries

- This position was created in 1991, working alongside the general secretary, to coordinate the work of the various agencies to reduce overlap and duplication of efforts. It was eliminated in 2004.

Executive director

- After the general secretary position was phased out in 2004, synod created this position, which combined responsibilities of the general secretary and of the executive director of ministries.

Canadian ministries director

- When the Council of Christian Reformed churches in Canada became the Canadian Ministries Board, the title of its senior leader was Canadian ministries director, (also named director of Canadian ministries in various structure iterations).

Task Force to Review Structure and Culture (TFRSC)

Synod 2011 appointed this group after the executive director parted ways with the denomination in 2011 and there was much angst and disillusionment of staff, particularly within the Grand Rapids office.

Ecclesiastical, Structure and Leadership team (ESL)

A group of Council delegates and senior staff appointed to address ecclesiastical, structural, and legal implications of the Canada corporation’s 2019 structural changes. (Now disbanded.)

Structure and Leadership Task Force (SALT)

A group tasked with ensuring that the position descriptions proposed by the ESL team were complete and compatible and to consider other relevant ecclesiastical considerations. Its proposal was approved by the Council of Delegates in May 2021, to recommend to synod. (The task force is now disbanded.)

Legal Structure

To add just one more layer of confusion, there are legal entities created to ensure compliance with Canadian and American laws. Those are CRCNA-Canada Corporation and the Michigan Corporation. (In the U.S., charities are incorporated at a state level, not federal). In the guide, these are referred to as Canada Corp and U.S. Corp.

The headquarters for Canadian operations of the CRCNA is in Burlington, Ont., and the U.S. headquarters is located in Grand Rapid, Mich.

About the Author

Gayla Postma retired as news editor for The Banner in 2020.