Several years ago, I was reading the parable of the Good Samaritan and trying to live it out in my life. The parable shapes and expands our definition of “neighbor.” Later that week, while walking through San José, Costa Rica (where I live), I came across a man lying in the gutter. It looked like he was dead. What was my responsibility to my neighbor? As I approached the man, some men called to me from the opposite side of the street, where they were sitting in the shade. “Don't worry,” they said. “He’s just drunk.” I blushed and hurried on.

I’m still not sure if that was the right thing for me to do in that situation, but I returned to the parable with a new question: How did the Samaritan know that the man he was helping wasn’t just drunk? The answer leaped off the page: The man was naked and had been badly beaten!

Our attempts to apply Scripture shape what we observe as we reread Scripture. The stakes are high. There’s a lot of pressure to interpret God’s word correctly. Disagreements about the meaning of Scripture can make us feel as if the very foundations of our faith are being undermined. It can be easy to conclude that the person in disagreement with me has stopped treating the Bible as authoritative.

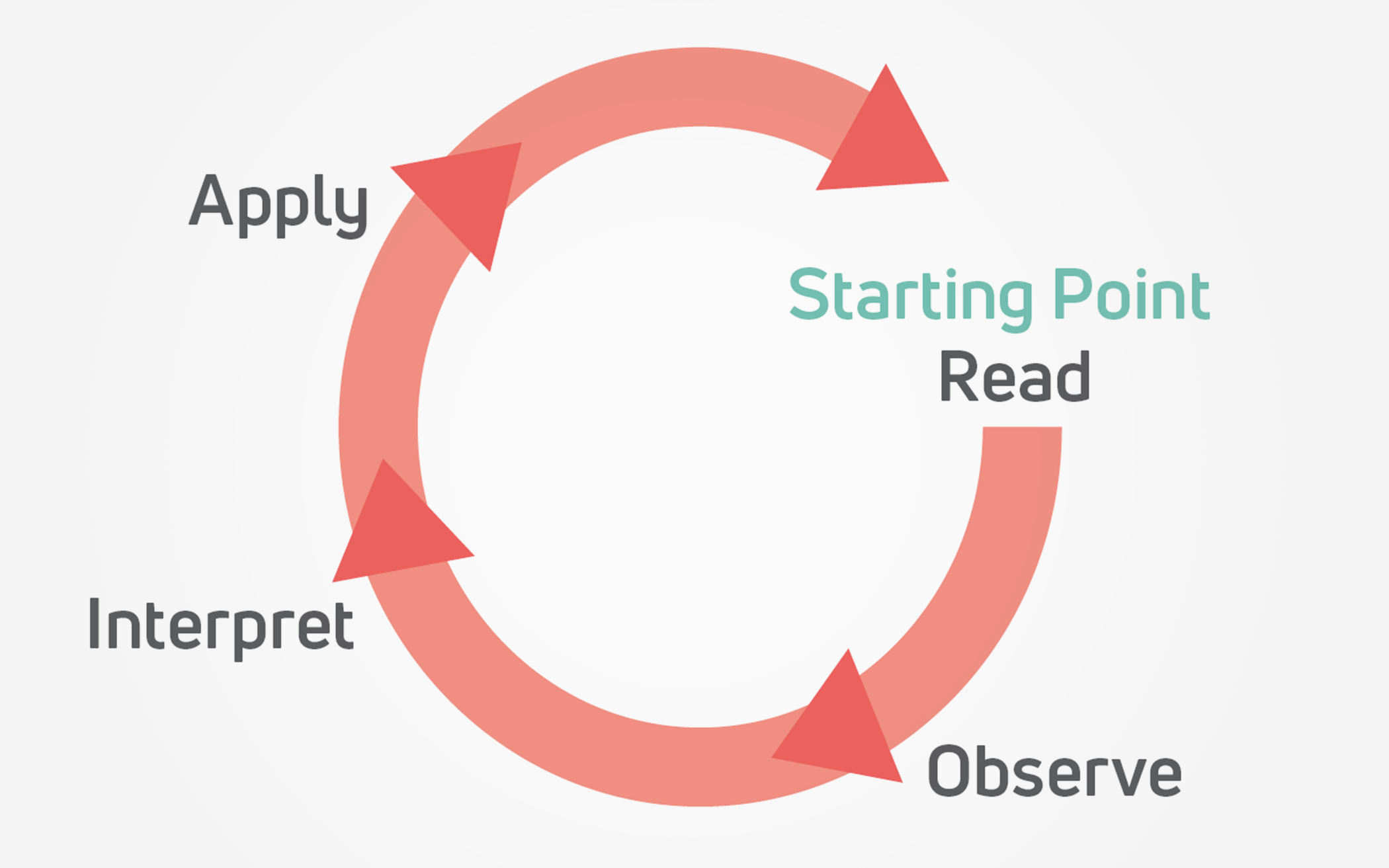

Have you ever noticed something new in a passage you were trying to apply to your life? Latin American theologians have been talking about this phenomenon for a while. The image below comes from a book by Catalina Padilla that has become a classic in Latin American theology: La Palabra de Dios para el pueblo de Dios (The Word of God for the People of God).

I grew up thinking of Bible reading as linear. You start off with the correct beliefs about the Bible. Then you read, guided by those beliefs. Once you have the correct answer, the only thing left to do is to apply that answer. Then you’re done! Just keep applying that answer.

But I think a more cyclical understanding of Bible reading better represents what actually happens when we read the Bible. If you have been applying Scripture to your life, the Holy Spirit’s work in you will cause you to change. With time, the things you notice about Scripture will also change. A person who devotes a year to living out the Sermon on the Mount will read it differently from someone else. Our experiences applying Scripture shape the sorts of things we observe as we reread Scripture.

This gives us options when we contemplate how two different people sometimes read the same text so differently. Has one of them abandoned a high view of Scripture? Are they using different principles when they read?

Perhaps. Or maybe they are just living in a radically different context that results in radically different experiences of applying Scripture, which leads them to observe different things as they read Scripture.

A pastor working in a conservative setting is more likely to have positive experiences applying the traditional view of human sexuality in their life and ministry. These pastors often see the fruits of the Spirit blossoming in the lives of same-sex-attracted people who commit themselves to celibacy. They also say they have an easier time pushing back on things like pornography use and polyamory. These pastors naturally bring these positive experiences with them to Scripture as they reread it.

Likewise, a pastor working in a more liberal setting often sees negative things resulting from the application of the traditional view of human sexuality, such as anxiety, bullying, depression, and self-harm. In a context in which those sorts of experiences are dominant, a pastor will be much more likely to return to Scripture with new questions: “Wait, are we missing something here? Is there something we’ve overlooked?”

The most basic rule of reading the Bible is that Scripture interprets Scripture. My professors covered this on literally my first day of seminary. According to this rule, we ought to use clear texts to interpret unclear texts. But I’ve seen precious little that defines what qualities make a text clear or unclear. It seems pretty subjective. Which texts are clearer: those that talk about sexual holiness, or those that show Jesus’ compassion toward the marginalized sinners of his day? Which “clear” texts do we use to interpret other “unclear” texts?

When we disagree with someone about what Scripture teaches, it could be that they have different beliefs about the authority of Scripture. But the difference might be the product of the fact that we’re working in different contexts, observing different things, and using different passages to be the “clear” ones that we use to interpret other passages.

Some might not be convinced. Here I’ll address some common criticisms:

1. “I prefer a more linear way of reading.”

If Padilla is correct—and I think she is—even people who think they read the Bible linearly are in reality doing something more circular. Your context shapes what you observe, whether you are aware of it or not.

2. “Won’t this result in a postmodern free-for-all where truth is anything you want it to be?”

Not necessarily. The old rules for Bible reading still apply. We just have a greater responsibility to be aware of how our context shapes what we read. Postmodernism in small doses is a helpful antidote to some of the less-helpful parts of modernism still flowing in our bloodstream. Absolute faith in our own objectivity doesn’t make us better readers of the Bible.

3. “Isn’t this just going to make us more worldly? We shouldn’t be adapting to accommodate the values of the culture.”

This is a valid concern. Worldliness is indeed a problem in all churches, including those that view their Bible reading as linear. But increasing our awareness of how our contexts shape our reading of Scripture won’t make us more susceptible to worldliness. It should actually make us more resistant.

I've read the Bible with people from all over the world. Without exception, everyone brings their cultural values with them as they interpret the Bible. People from more individualistic cultures end up with more individualistic interpretations of the Bible. The same goes for people from more community-focused cultures. There is nothing quite like listening to a dedicated capitalist and a committed Marxist try to talk together about what Jesus had to say about money. Denying the fact that our contexts influence our readings of Scripture is no protection from worldliness.

It’s important for us to be aware of how our own contexts affect our reading of Scripture. Juan Stam, another Latino theologian, regularly compared reading the Bible to looking through a dirty window. You need to clean your own side (understand your own context) and the other side (understand the historical context) to see clearly.

My own beliefs about human sexuality lean traditional. But I recognize that has a lot to do with my living and working in a conservative environment. I’ve largely been insulated from seeing the sort of suffering among LGBTQ+ Christians that my more liberal colleagues have seen. But I am starting to see this suffering more clearly.

For now, traditionalists (myself included) are saying that this suffering is a result of bad application. It isn’t that we are interpreting the Bible poorly; it’s that we’re applying it poorly. The logic is that some small changes (e.g., better pastoral care, intentional inclusion of singles, and not treating same-sex relationships like an extra-evil sin) will make it easier for LGBTQ+ Christians to thrive in conservative churches. The window of opportunity is closing for the conservative church to show that this is indeed true.

The best available data currently show that people who are LGBTQ+ experience a higher risk of depression and self-harm when in non-affirming spaces. If that doesn’t change soon, a growing stream of people will return to the Bible to ask, “Wait, are we missing something here?”

Discussion Questions

- Describe an instance when your understanding of a Scripture passage changed. How did your reading change? What influenced your reading?

- What do you know about the rule of “Scripture interprets Scripture”? How have you used it before? Do you agree with the author’s difficulties with the rule? Why or why not?

- What do you think of the cyclical understanding of Bible reading presented in the article? Do you see this as a helpful view? Why or why not?

- “It’s important for us to be aware of how our own contexts affect our reading of Scripture.” How would you describe your own context? How might it affect your reading of Scripture?

About the Author

The Rev. Micah Schuurman has been serving for 10 years as a partner missionary with Resonate Global Mission. He lives in Costa Rica, where he teaches Old Testament and Hebrew at La Escuela de Estudios Pastorales (the School of Pastoral Studies). He blogs at integralmissions.wordpress.com.