After years of documenting “Back Row America,” Chris Arnade doesn’t have any answers. He doesn’t know how to solve poverty, stop drug addiction, or end racism. In fact, as he notes in his astonishing book of photo-journalism, Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, it’s all too easy for us in the front row to hold opinions on these matters without ever meeting someone whose life is entangled with these difficulties. Rather than offer answers, then, Arnade wants us to simply see those who we’ve relegated to the margins. As he writes, his work is “about reconsidering what is valuable, about honoring aspects of life that cannot be measured, and about an attempt to listen and look with humility.”

Arnade himself began “to see the country differently” when he wandered into the Bronx one day in 2011. Accustomed to taking long walks to reduce the stress of his work as a bond trader on Wall Street, and becoming increasingly disillusioned with his line of work since the financial crash, he found himself drawn to a place he had always avoided: “I was told it was too dangerous, it was too poor, and I was too white.”

And while he notes that “it was loud, dirty, and filled with exhaust,” what struck him even more forcefully was its “strong community and sense of place.” In fact, he was so drawn to these aspects of the Bronx that he found himself spending more and more time in the neighborhood of Hunts Point, befriending members of a street community that included prostitutes, pimps, drug dealers and users. He began interviewing anyone who would talk to him and taking their pictures, and eventually, he gave up his regular job—and income—in order to travel the country in search of similar communities in Selma, El Paso, and Milwaukee, among others.

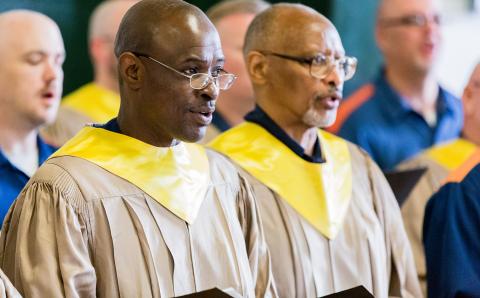

In each place, Arnade encountered the same hardships—racism, unemployment, and drugs—as well as the same sources of hope, particularly in the ways he saw people forge community in barbershops. In Walmart parking lots. In McDonald’s. And in store-front churches. He devotes special attention to these latter two, arguing that while many of us wouldn’t be caught in either, such spaces provide essential needs for those in back-row America.

In these particular chapters, Arnade’s interviews and pictures capture the tensions of his subjects’ lives. You feel it as you turn from a picture of a man on his knees praying on one page to a woman smoking crack on the next. Or when one of his interviewees tells him how she would like to be described: “As who I am. A prostitute, a mother of six, and a child of God.”

This woman’s answer communicates her hardship. In it, though, you can also hear a sense of hope, a longing for dignity—and this, ultimately, is the book’s greatest strength: it doesn’t flinch from reality, but it shows us more than despair. Ultimately, Arnade helps us see those we often would prefer not to; even more impressively, he does so without reducing them to morality tales or items of merely academic interest. Sure, his book might hint at some lessons, but it most powerfully teaches a holier lesson—a lesson about the dignity we are all imbued with, including "the least of these.” (Penguin/Sentinel)

About the Author

Andrew Zwart lives in Grand Rapids, Mich., and is director of interdisciplinary studies at Kuyper College. He enjoys gardening, impromptu dance parties with his wife and two boys, and taking walks while listening to podcasts.