My third-grade teacher once told our class, “Most of you will never have a biography written about your life.” The year was 1988, and the assignment was to write a book report on a famous person. This was my teacher’s overly pragmatic explanation of the biography genre.

Growing up, that proclamation stuck with me, and the older I got, the more I believed it. “Who would want to read about my life as a Korean American immigrant kid? What’s so special about our family?”

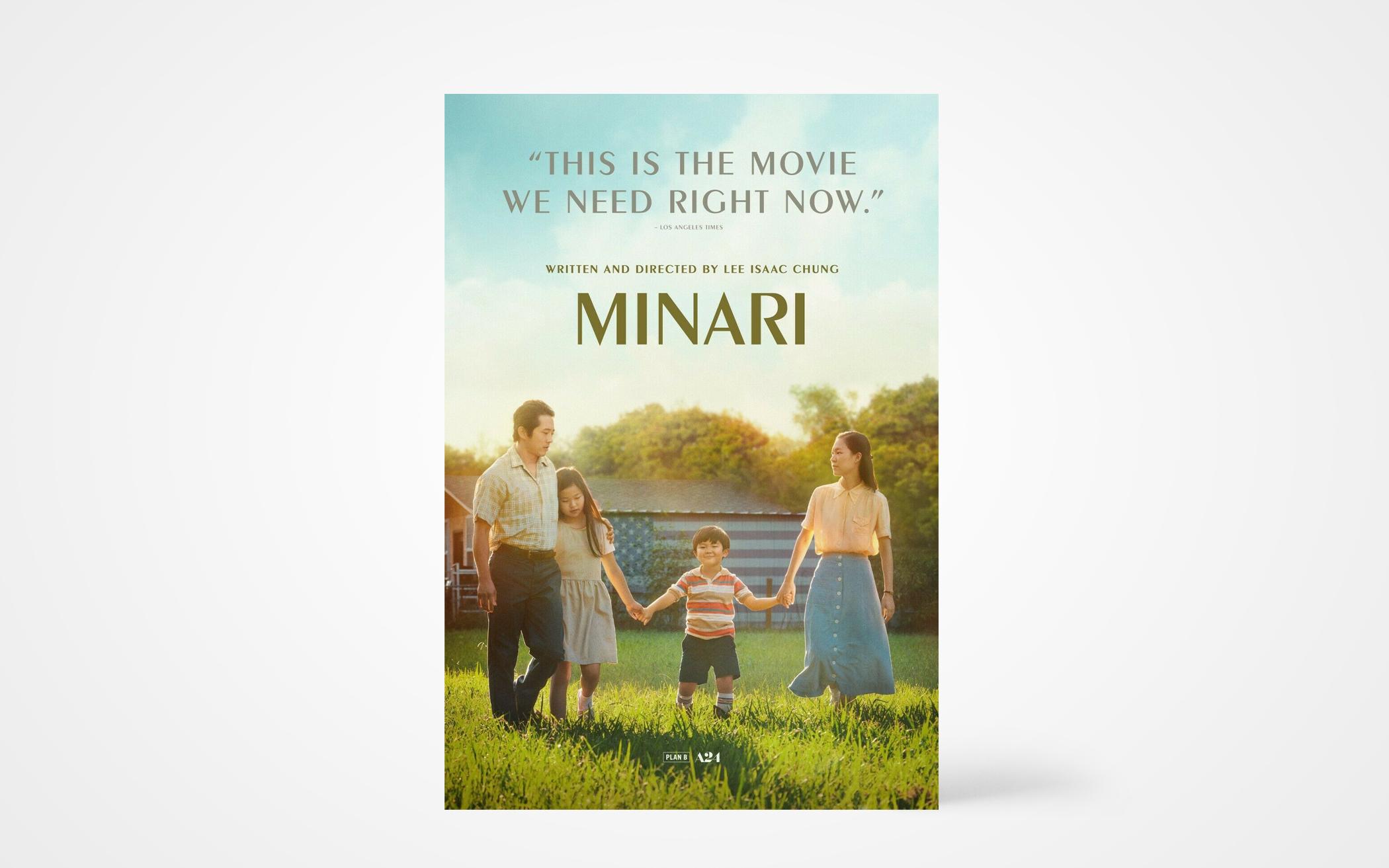

Lee Isaac Chung, writer and director of the movie Minari, thought otherwise.

Minari, set in the 1980s about a Korean family leaving the big city to stake out their portion of the American dream in rural Arkansas, is a movie that connects with a much broader audience than its name would suggest. You do not have to have tasted hanyak, a traditional Korean homemade medicine, to relate to little David’s (played by Alan Kim) disdain for it. You do not have to have a grandmother who “smells like Korea” to be pained by the generational struggles within a family unit. You do not have to know Korean, the movie’s primary language, to understand the marriage hostility between Jacob and Monica (played by Steven Yeun and Yeri Han, respectively).

But what makes Minari special, especially for the Korean American community, is that for the first time, this movie feels like a biopic for our collective American experience.

In one particular scene, Monica asks another Korean American lady at the chicken farm where she works, “Why hasn’t anyone started a Korean church here?”

Her friends respond, “The Koreans around here, we left the cities on purpose … to escape the Korean church.”

So they go to an “American” church where their daughter, Anne (played by Noel Cho) is quizzed by a Caucasian girl in a scene all-too familiar for Korean Americans. Anne’s new friend instructs her to “stop me until I say something in your language.” Where she begins to speak gibberish until she arrives at a word that catches Anne’s attention.

“Wait, you said ‘komo.’ That means aunt.”

“Cool.”

This scene represents one of the greatest strengths of the movie. Instead of centering these sorts of microaggressions at the forefront of the narrative, Lee Isaac Chung presses forward. Racism is a very minor cast member, not the starring role, of the Korean American immigrant experience.

For many Korean Americans in the Church, this scene also represents the disillusionment we have with being Christian in America.

Leaving the Korean church.

Not quite adapting to the American church.

Leaving one group of people only to find that you don’t quite fit in with the other. That is the quintessential Korean-American faith story.

Minari gives voice to that disillusionment but with the hope that, like the resilient vegetable for which the movie was named, our story also will have its place in the orthopraxy of our shared faith.

About the Author

Daniel Jung is a graduate of Calvin Theological Seminary and an ordained pastor in the Presbyterian Church in America. He lives in Northern California, where he serves as an associate pastor at Home of Christ in Cupertino.