The Banner has a subscription to republish articles from Religion News Service. This story by Fiona André was published Dec. 18, 2024 on religionnews.com. It has been edited for length and Banner style.

A report by Pew Research Center on international religious freedom named Egypt, Syria, Pakistan, and Iraq as the countries where both government restrictions and social hostility most limit the ability of religious minorities to practice their faith.

The report, now in its 15th edition, uses two indexes created by the center in 2007—the Government Restrictions Index and the Social Hostilities Index—to rank countries’ levels of government restrictions on religion and attitudes of societal groups and organizations toward religion.

The GRI focuses on 20 criteria, including government efforts to ban a faith, limit conversions and preaching, and preferential treatment of one or many religious groups. The SHI’s 13 criteria take into account mob violence, hostilities in the name of religion, and religious bias crimes.

The study looked at the situation in 198 countries from 2022, the latest year for which data are available from such agencies as the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, the U.S. Department of State and the FBI. The report also contains findings from independent and nongovernmental organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Anti-Defamation League, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International.

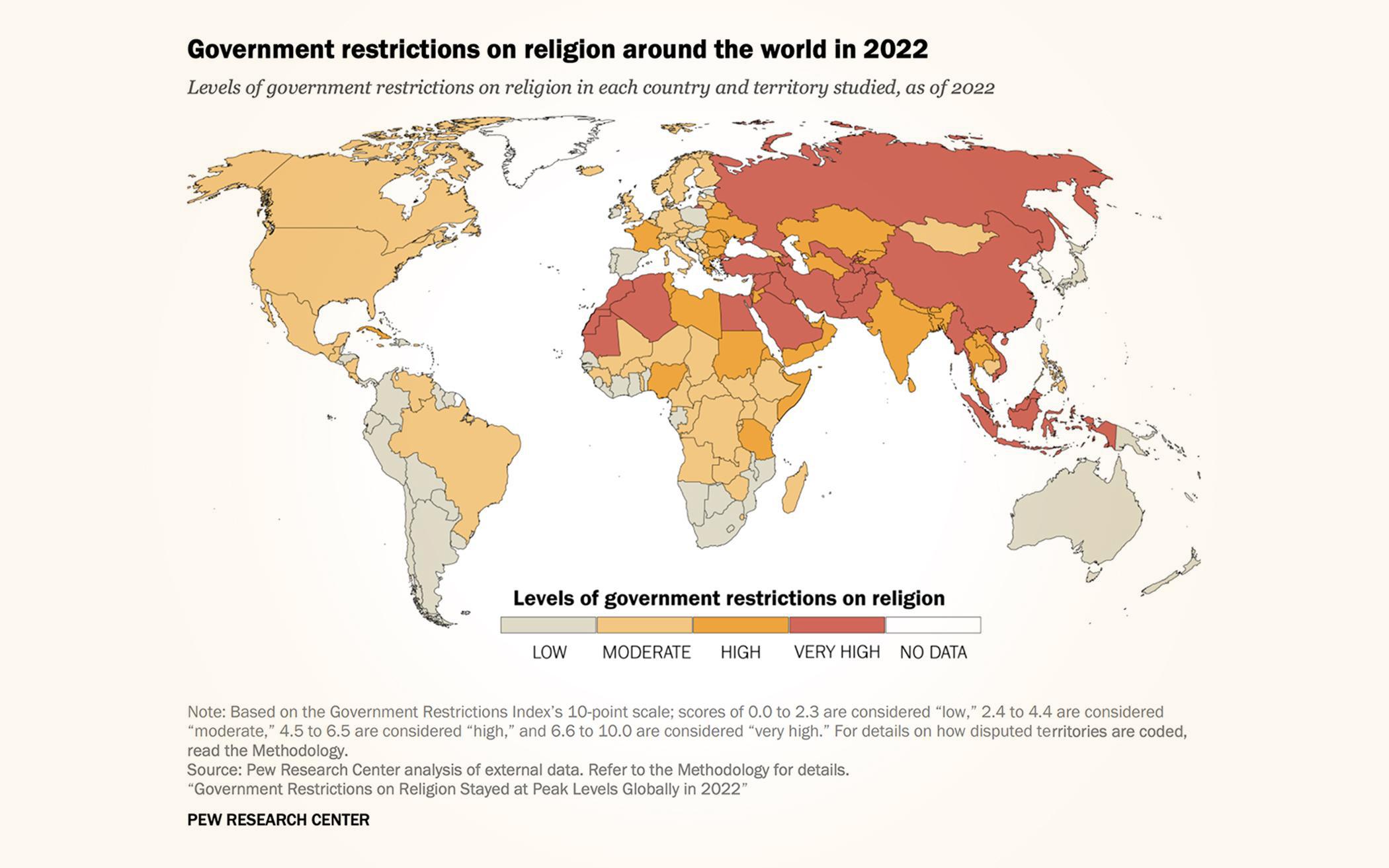

In total, 24 countries were given high or very high GRI scores (4.5 or higher on a scale of 10) and high or very high SHI scores (higher than 3.6 out of 10).

Thirty-two other countries, including Turkistan, Cuba, and China, scored high or very high on government restrictions, but low or moderate on social hostility. Most were rated as “undemocratic” and “authoritarian” by The Economist magazine’s Democracy Index.

“Such regimes may tightly control religion as part of broader restrictions on civil liberties,” reads the report. Many Central Asian countries and post-Soviet countries fell into that category, noted Samirah Majumdar, the report’s lead researcher.

Besides ranking countries where religions were under the most pressure, the team that put together the report, part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project, tried to determine “whether countries with government restrictions tend to be places where they also have social hostilities. Do countries with relatively few government restrictions also tend to be places where they have relatively few social hostilities?” explained Majumdar.

Majumdar said that the results were inconclusive. “We can’t exactly determine a causal link, but there are some patterns we were able to observe in the different groupings,” she said. “A lot of those countries have had sectarian tensions and violence reported over the years. In some cases, government actions can go hand in hand with what is happening socially in those countries.”

Countries with low or moderate scores on both indexes—a GRI no higher than 4.4 out of 10 and an SHI between 0 and 3.5—usually had populations under 60 million inhabitants.

The index factors the same criteria over the years, and the team relies on the same sources, allowing for comparisons from one year to another. From 2021 to 2022, median GRI and SHI scores stayed the same, but in sub-Saharan Africa, the GRI rose from 2.6 to 3.0 out of 10. In Middle Eastern and North African countries, the index went from 5.9 to 6.1.

Among the 45 countries that presented high or very high scores on the Social Hostilities Index, Nigeria was the highest of seven countries with very high levels, a result linked to gang violence against religious groups and violence by militant groups Boko Haram and ISIS-West Africa.

Iraq has seen its social hostility score increase. The report attributed this to violence against religious minorities imprisoned by Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces. It also cited a 2024 Amnesty International report on outbreaks of gender-based violence in Iraqi Kurdistan, with many occurrences of women being killed by male family members, sometimes for converting to another religion.

According to the report, physical harassment against religious groups by government or social groups peaked in 2022. This category covered acts from verbal abuse to damage to an organization’s property, displacements, or killings. The study noted 26,000 displaced people from Tibetan communities in China and continued gang violence targeting religious leaders in Haiti.

Overall, the number of countries where physical harassment took place increased to 145 in 2022, up from 137 countries in 2021.

c. 2024 Religion News Service

About the Author

Religion News Service is an independent, nonprofit and award-winning source of global news on religion, spirituality, culture and ethics.